Their noses are swabbed. Their exams are recorded. Their Instagram posts are monitored.

During the pandemic, college students are surveilled very, very closely.

The health crisis has introduced new forms of data collection into higher education, but these are largely changes of degree, not kind. For years now, tech companies have been selling colleges tools that collect information about how students learn, where they travel on campus and what they do online. Such technologies promise to detect patterns that can improve teaching and graduation rates, ensure safety and even predict who is likely to succeed.

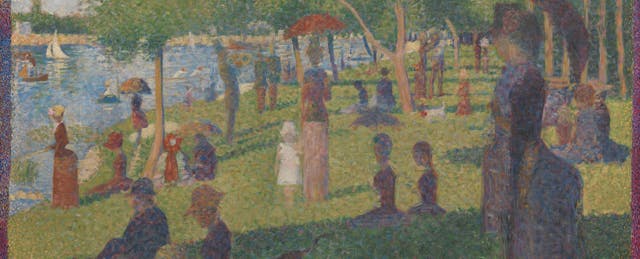

But there’s also growing recognition that this kind of tracking can distort perceptions, like a pointillist painting. Stand up close, and you see little more than a collection of data points. It’s not until you take a few steps back that the full student—a complex human—comes into view.

And these humans have opinions about all the data their colleges collect from them. According to a new report from think tank New America and the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, students want transparency. They want privacy. They want a say over how their information is used.

Some educators and institutions are listening, and responding. They’re communicating more clearly about how and why they use data and recruiting students to help create tech policies and tools. The hope is not only to avoid blowback, but also to design systems that work better for everyone.

“I’m an advocate for privacy and student-centered design because I think that makes for more relevant and responsive edtech, and ultimately more useful edtech,” says Carrie Klein, senior fellow and higher education lead on the Future of Privacy Forum’s Youth and Education team. “Institutions are going to benefit from that.”

Advocates say students stand to benefit, too—as does everyone else who cares about personal rights in the digital age.

“I believe strongly in privacy. I believe it’s as fundamental as the right to vote,” says Ravi Pendse, vice president for information technology and chief information officer at the University of Michigan. “We should have a right to privacy.”

Trust Starts With Transparency

From protests about facial recognition tools on campus to outcry about remote exam proctoring services, college students are speaking out against edtech that feels invasive and punitive. These recent movements align with studies from the last half-decade showing that college students who grew up exposed to the internet care about maintaining their digital privacy.

That’s echoed in the report published March 10 about student perceptions of data use within higher education. It found that students tend to trust their colleges more than tech companies. Yet they still are uneasy about a lot of the data collection that colleges do, even when those practices are intended to improve academic outcomes and maintain safety.

It’s an example of the challenge that exists in an open society to balance security and privacy, Pendse says. But in higher education, he adds, maintaining student trust is essential.

“We work on trust that is built among each other,” Pendse says. “That’s huge, that’s important, and we have to respect that.”

Recommendations about how to foster student trust when it comes to data emphasize the importance of clear communication. Yet university data privacy policies typically are hard for students to find and written in jargon difficult to understand, Klein says.

“There’s a lot of space for growth and improvement to have clear standards so students understand—here’s the data integrity process that we have in place on campus,” she says. “It gets beyond thinking of data as security and compliance to ensuring a level of agency students have over their data.”

So the University of Michigan is working to set a new standard for transparency. At the end of January, on international Data Privacy Day, it began promoting ViziBLUE, a new online guide to how the university collects, uses and shares student information.

It features resources written in plain language about all the data processed at an institution of higher learning, from admissions, academics and finances to library services, Wi-Fi location and video conferencing. There are links for ways to take action, such as opting out of tracking or downloading personal profiles, and an email address to contact the university’s privacy office.

When Pendse’s team consulted with students to develop the site, he was impressed that they were “extremely conscious of the privacy aspects, very well informed and very knowledgeable about the challenges of being on the internet.”

Plus, students asked Pendse compelling questions that he says he learned from.

“We are determined to show the entire world how this could be done potentially the right way, with input, with our constituents,” he says. “It’s going to take everyone thinking thoughtfully to come up with a privacy paradigm we can all respect and be comfortable with.”

Treating Students as Co-Creators

Klein lauds the University of Michigan’s work on transparency. And she also issues a challenge: Colleges should not only inform students about data policy and tools, but actually include them in creating data policy and tools.

“It’s really important to have an inclusive data governance process that can start to speak to some of the challenges and the evolving nature of data use on campus,” Klein says. “Having a really robust process includes student advocates, and students themselves can really help determine what looks appropriate.”

A research project Klein conducted as a graduate student offers an example of how to treat students as data co-creators and users, rather than just data points. The work focused on creating an open-source analytics tool for teaching and advising. Such systems are intended to improve student outcomes, but they sometimes have the opposite effect, and so Klein and her colleagues wanted to find out how students make sense of these tools.

Through focus groups with more than 80 undergraduates, they discerned that students were less likely to use and trust edtech tools that aren’t relevant to their needs, aren’t accurate for their individual circumstances and don’t display information in ways they can easily understand. And students were turned off by predictive analytics that seem to limit their options.

“Students, like everybody, we want to hear what our potential is,” Klein says. “We don’t want to hear what we can’t do.”

Additionally, the research team employed student developers to help design some of the tools they tested with student focus groups. Those turned out to be the systems that participants preferred.

“By incorporating students into the design, we actually came up with a dashboard design that felt much more relevant to the students we interviewed,” Klein says. “If we aren’t including the end users all the way through the lifecycle of development, design, implementation and adoption, while they may use the technology, it may not be as relevant to them as if their perspective had been included early on.”

Getting students to actually use edtech tools is a short-term goal that may persuade college leaders to seek more student input about data policies and practices. But there’s an even better reason for it, Klein says: It fits within the mission of higher education.

“Given that data is increasingly part of our public and individual daily lives,” she says, “the more we can do to support student knowledge, development and agency in this area, the better off we will all be in the end.”