Penny Fox didn’t finish high school. A single mom of two kids, the jobs that she can find tend to be in retail, at stores like Walmart and Home Depot.

But Fox wants work that is better paid. She wants a career. To get one, she’s been taking classes at an Arizona community college—off and on—for 10 years.

“I was a foster-care child,” Fox says. “I slip back and forth into a bad mental state, and I don’t always finish what I start. I’m trying to change that.”

What would it take for a college to really support that change?

It’s a question that Pima Community College and the Women’s Foundation for the State of Arizona are trying to answer. Since 2020, they’ve run a pilot program, called Pathways for Single Moms, that offers wraparound services to help low-income women who are raising children to pursue stable careers by earning college credentials.

Not just any credentials, however. Specifically workforce training certificates that align with industries in Arizona that are hungry for workers and that pay “family-sustaining wages.” That means pay high enough to “make those families self-sufficient and not have to look back to public benefits,” says Amalia Luxardo, CEO of the Women’s Foundation for the State of Arizona. For a single parent with a preschooler in Pima County, the foundation calculates that wage to be about $42,000.

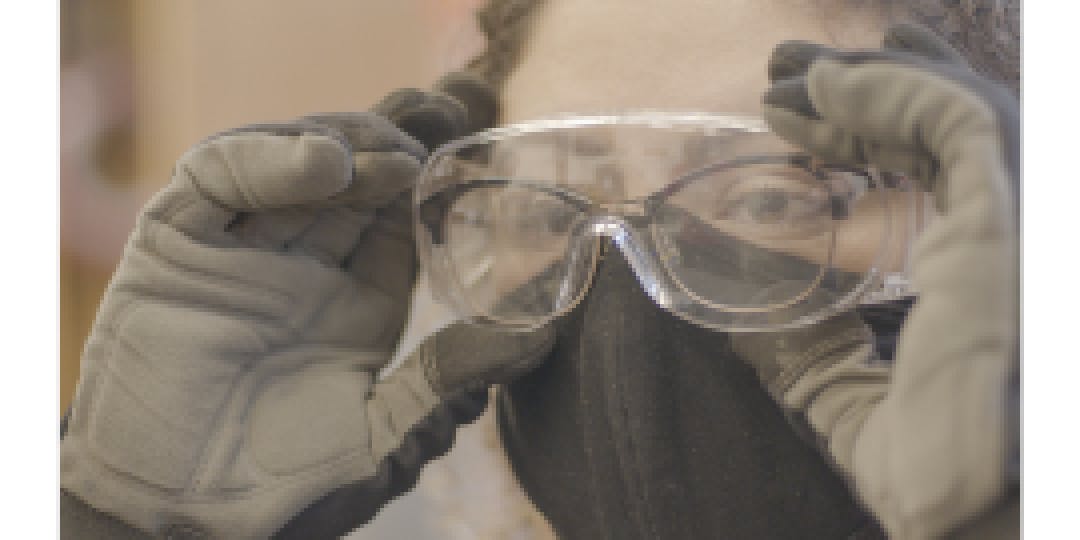

Programs at Pima Community College that fit the pay and employment criteria include automated industrial technology; building and construction technology; information technology; and logistics and supply chain management.

If those sound like surprising career tracks for women, that’s not accidental. The Pathways program encourages mothers to enter industries that tend to employ more men—because those industries tend to pay better. They’re also fields where it only takes about a year to earn the entry-level certificate. Anytime a parent has gotten that credential, Luxardo says, “it really sped up the track of these families being able to get out of the margins.”

The Pathways program offers student-moms academic aid, covers their tuition costs, and pays them a stipend. It also helps with what can be a significant barrier for single mothers trying to go back to school: finding child care. Program leaders even fought successfully to change a state law so that parents pursuing higher education are eligible for public child care subsidies.

As the outcomes from the first year of the Pathways program show, not even all this support is sufficient to ensure that women like Fox can complete workforce training efficiently, affordably and without undue stress. (The coronavirus pandemic hitting soon after the program launched didn’t help, either.)

But even if earning a credential takes longer than expected, a program like Pathways for Single Moms makes that goal—and the larger mission of changing your life—seem possible, says Monique Ortega, a parent who is studying supply chain management through the program.

“I felt like it gave me confidence to not give up on myself, and I feel like that’s just one of the things a lot of moms go through: We don’t feel like we’re capable of doing these things,” she says. “It makes it easier, knowing that you’re not alone. They’re rooting for you.”

Support for Single Moms

Getting by is difficult for millions of single mothers in the U.S. As a group, they have less education and lower incomes than other women and other mothers. As of 2019, about half of young single moms made less than $30,000 a year.

In Arizona, 70,000 single moms working full time before the pandemic didn’t have an associate degree or a bachelor’s degree, according to research from the Women’s Foundation for the State of Arizona. More than 30,000 working single moms had only a high school diploma. The kinds of occupations they tend to enter offer median wages under $30,000, including customer service representative, secretary, retail sales supervisor, cashier and medical assistant.

Leaders at the foundation and at Pima Community College know that a certificate or advanced degree could make more of Arizona’s single moms eligible for better pay and less likely to experience poverty. But for those same women, finding money to pay for and time to attend college courses can be a challenge.

Participants in the Pathways program don’t always know where their next meal is coming from, or where they and their kids are going to sleep in the days ahead. Most receive public assistance, like food stamps. Many have debt, including student debt.

“It’s not uncommon to hear the team come in and say, ‘so and so is homeless as of tomorrow,’ or living in her car,” says Laurie Kierstead-Joseph, assistant vice chancellor at Pima Community College for adult basic education for college and career.

And some participants endure other hardships as well. When Fox heard about Pathways for Single Moms, she was living with her children at a shelter for abused women.

That was one of the social-services organizations that college and foundation leaders turned to when trying to recruit up to 20 women for the first Pathways cohort, which started in January 2020 in courses for automated industrial technology and logistics and supply chain management. Program leaders also identified eligible students who were already taking courses at Pima.

“Recruitment can be challenging, even though there’s a huge need out there,” says Kierstead-Joseph.

A dozen women ended up enrolling in Pathways that semester. The women’s ages ranged from 22 to 37. At least nine of them had children under age six. Seven of them identified as Latina, two as African or Caribbean, one as multiracial, one as Caucasian and one as “other.”

Upon starting Pathways, the first type of support student-moms receive is academic. Their courses use Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training instruction, a model that helps students strengthen their math, reading and writing skills while they prepare for a career. People who participate in IBEST courses, whether they came in with a high school diploma or not, have better completion rates than other students, notes Kierstead-Joseph.

Fox appreciates the teaching she’s received through Pathways IBEST courses, which she says is better than the instruction she had in other courses she took in the past.

“When I ask for help, they will help me,” Fox says. “If I have a question, they don’t get impatient.”

Another form of support is financial. Tuition for women in the program is paid by the foundation. Students receive a monthly stipend, which started at $416 but moved up to $815 in November 2021 due to rising costs of living. An emergency fund is also available, which some participants have used to pay bills, buy food and, in one case, retrieve an impounded car.

More support comes through relationships, both with advisers at the college and foundation and with other student-moms. Program leaders hope participants form a network they can draw on as they embark on new careers—as well as a community that offers them a sense of belonging.

To facilitate that bonding, Pathways leaders host workshops and activities that bring student-moms and their kids together.

At a fall gathering in a park, “one of the things we thought of was, a single mom is always the one taking the picture of their kiddos, and maybe never has pictures of themselves,” says Emily Wilson, program manager of Pathways for Single Moms. “We brought in a professional photographer to take family photos for them, to help make their whole experience a little better.”

Finding Child Care

Before Ortega enrolled in Pathways, she had tried studying to be a paralegal. She also tried training to be a nursing assistant.

“It didn’t work because it’s not for people like me,” she says of those programs. “I needed to work, I needed to be able to pay my bills and have my kids in child care, and everything—it was just so hard.”

Finding reliable, affordable child care is an impediment for many single mothers trying to continue their studies. Some community colleges have child care available on their campuses, but the number offering that has been shrinking.

In Arizona, a law provided a subsidy for low-income parents to use for child-care costs, but it required them to work 20 hours a week to get the benefit. That conflicted with the goal that leaders of Pathways had for student-moms: that they study full-time in order to earn their certificates faster and then rejoin the workforce with better-paying jobs.

“We all know 20 hours a week at a dead-end job that doesn’t pay well isn't going to do much for these families,” Luxardo says. “We need to lift the weight of child care off these families so they can focus on getting a career, so they wouldn’t need those benefits again.”

So the foundation successfully pushed to get the law changed in spring 2021.

Until that rule change takes effect, though, the foundation secured funds to help Pathways participants cover the costs of sending their children to high-quality child-care providers.

But it turned out that this support didn’t necessarily benefit the student-moms. Among women in the first cohort, some had children old enough for school who didn’t need day care. Other women already had their own arrangements at child-care programs. Some preferred to leave their children with relatives and friends—despite this care not necessarily meeting official standards for “high quality.” And still other mothers couldn’t find open spots in a convenient, approved center, perhaps partly due in part to the pandemic’s effects on the early learning sector.

“You gotta find one in your area [that] takes both of your children—and sometimes there is not an opening for specific ages,” Ortega says. “I made sure before I started, I had the child care ready to go.”

Pathways leaders are figuring out ways to make high-quality child care more appealing and accessible to student-moms. Among the 20 new women enrolled for January 2022, about half are interested in taking advantage of this kind of support, Wilson says.

And by the end of the year, Pima Community College is slated to open a child-care center on one of its campuses.

Measuring the Results

Soon after the spring 2020 semester started, the pandemic hit. College courses moved online, child care grew scarce and student-moms found much of their lives disrupted.

Despite the unexpected change in conditions, the first cohort of Pathways for Single Moms was evaluated by the Community Research, Evaluation, and Development team at the University of Arizona.

Of the 12 women who started, three withdrew in the first semester. Three successfully completed certificate requirements within the year—the intended timeframe. Four women who didn’t finish the program on time have returned to complete their certificates.

The evaluation found that participants’ food security generally improved during the year. The program stipends proved to be an important source of income for them.

But there were challenges. Several students felt they struggled with math coursework. College and foundation leaders had trouble managing the caseload of student-moms and providing all the help they needed to succeed.

The report raises a question: “Is there a defined threshold of stability and readiness that a potential participant needs to meet to be accepted into the next cohort?”

Fox still has classes to finish. “I haven’t told anyone I’m behind yet,” she says. “There are loads of homework to do every week. I don’t feel like it’s enough time.”

Ortega also struggled to keep up the pace, and she had to retake some classes. But eventually she did earn her certificate—and decided to keep going. She’s now pursuing an associate degree in supply chain management.

“It really encouraged me to not stop,” Ortega says.

When Ortega earns that degree, she knows she’ll have options. She’s thinking about what opportunities speak to her. Although she knows some of her classmates want jobs at Amazon, she’s considering roles at a food bank warehouse, in part because she currently volunteers at a diaper bank.

“It’s always good to give back to people,” Ortega says. “Obviously I do need to support my children, but I also want to do something I love.”