Child care concerns have reached a boiling point for parents and providers, and it’s become increasingly difficult for families to afford essentials like health care and housing.

Those are among the top findings outlined in a special anniversary report from the RAPID Survey Project at the Stanford Center on Early Childhood, which highlights data from a survey that asked caregivers of young children what they want their policymakers to know about how they are doing and what they need. RAPID has received almost 30,000 responses.

The report comes as a U.S. presidential election — one that RAPID leaders say has major implications for children and families — looms less than five months away.

It also comes nearly four years after the RAPID project’s launch in April 2020. Since then, more than 20,000 parents of children under age 6 and nearly 7,000 child care providers — spanning all 50 states, a range of child care settings, and both English and Spanish language speakers — have responded to RAPID’s monthly surveys. The findings provide intimate, continuous snapshots of the experiences and emotional states of the adults who are most present in the lives of young children.

Parents and providers are given two different surveys, but their concerns are “remarkably similar,” says Cristi Carman, director of the RAPID Survey at the Center.

Their responses can be distilled into a few ideas. “The throughline across all of them,” Carman notes, “is that families need more economic stability.”

Child Care Is a Top Concern

Regardless of demographics, family structure and income, parents are concerned about child care — affording it, accessing it, and ensuring that it’s safe and high quality. That’s the biggest challenge they want their elected officials and other policymakers to know about.

“There is a serious child care crisis in our country,” wrote one parent in South Dakota. “We are making it difficult for families to live on one income, and families that need child care can’t find affordable child care.”

A parent in Maryland said: “There are nearly no options locally for child care for an infant under two. My husband and I both have full time jobs and expect to continue working, but this could possibly force one of us from our jobs if we can’t find child care.”

Child care providers, which include early childhood teachers and directors in center- and home-based settings, are also very worried about being able to meet parents’ child care needs.

“Educated, experienced, passionate teachers aren't able to stay in this field because they literally can't afford to,” wrote a center-based teacher in Wyoming. “I've got parents dropping out because they can't pay tuition, and neither can the parents that are also teachers here.”

Many providers mentioned the need for the government to invest more money in the early care and education system, including one in Wisconsin who said, “As an in-home provider, I do not even bring home minimum wage, as my parents can’t afford to pay that much.”

This concern has had slight ebbs and flows over the last few years, but since last fall, it has become acute, according to survey data.

That’s likely because many families felt immediately and intensely impacted by the end of the $24 billion in child care stabilization grants that had bolstered early care and education providers after the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act. Those grants began to expire in September 2023, and as a result, many child care programs were forced to raise tuition prices for families.

“We know parents don’t have any room to pay more for child care, and yet that’s what is being asked of them,” says Carman.

Economic Instability Has Increased

Many families report that it has become more difficult to meet their basic needs, particularly in the areas of health care and housing.

Whether families are looking to rent or buy, housing costs have risen so steeply in the last couple of years that many find their situations untenable.

At the same time, the government programs that were rolled out during the height of the pandemic — such as food assistance, stimulus checks and the expanded Child Tax Credit — have disappeared, leaving some families worse off than they were before.

The expanded Child Tax Credit, which was passed under the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021, temporarily provided payments of $3,600 to tens of millions of families with children under age 6. It reduced child poverty in the U.S. by nearly half, bringing the rate down to about 5 percent.

With that program, “We really saw the most dramatic drop in levels of hardship,” says Phil Fisher, director of the Stanford Center on Early Childhood. Families used the money toward housing costs, to pay off student loans, and to cover basic expenses such as utility bills and groceries, he adds. But once it ended, challenges such as food insecurity soared.

“We definitely can detect [in the data] the way in which these large-scale economic policies are making a difference in these households,” Fisher notes, “and the way in which they are impacted when they go away.”

Those undulations can have a significant impact on children and families. Economic instability leads to emotional distress among adults, explains Carman, and emotional distress can harm children.

“It influences external factors like our behavior and the way we feel during the day,” she says, “which can undermine that connection and attentiveness we hope all caregivers can bring to their relationships with young children.”

A Crisis of Faith

On top of these worries and challenges, parents expressed skepticism that their elected leaders and other policymakers would push through any changes that meaningfully — and sustainably — improve conditions for children and families.

“We can’t rely on anyone but ourselves,” one parent in Mississippi wrote.

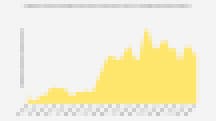

The frequency with which parents have reported feeling frustrated by their leaders’ inaction on issues relating to children and families has risen over the years, the RAPID surveys revealed.

“Everyone in charge only cares about themselves and making themselves richer,” a parent in Florida shared. “No one is ever going to help out the rest of us. It is what it is.”

“Families feel increasingly pessimistic about policymakers’ ability to take action and create the solutions that will really support their families,” Carman underscores. “That is at stake” in this election.