“U.S. Department of Education ends Biden’s book ban hoax.”

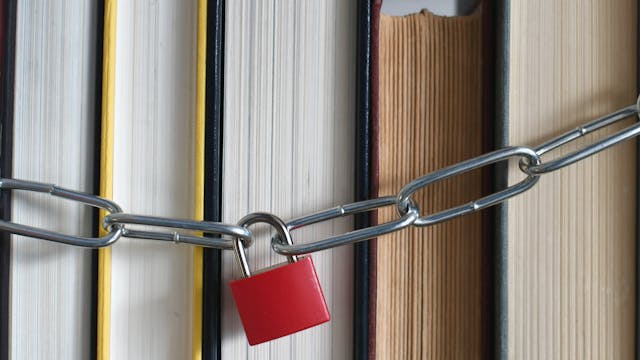

That headline from a recent press release by the federal agency has sparked outcry from free speech advocates and teachers who dispute that President Joe Biden’s administration exaggerated the pervasiveness of book bans in the nation’s schools. In fact, educators say they’ve been subjected to censorship for years.

Among them is Ayanna Mayes, a librarian who has spoken out about the books, particularly by Black and queer authors, purged from the shelves of the library she oversees at Chapin High School in Chapin, South Carolina. “The state-sponsored removal of information from schools is not a hoax,” she said during a recent call announcing a complaint against her state for its curriculum restrictions.

“There is no way to deny that our state and school districts have thwarted mine and my colleagues’ efforts to provide the highest quality education to our students without blatantly calling us liars,” Mayes said. “We have experienced what we say we have experienced. We have witnessed what we say we have witnessed.”

The Legal Defense Fund (LDF), a legal and racial justice nonprofit, filed its federal civil rights lawsuit against South Carolina just days after the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights suggested in a January 24 press release that claims of book banning are baseless and that school districts have simply removed books that are “age-inappropriate, sexually explicit, or obscene materials.” The agency said that it was reversing Biden administration guidance that reading restrictions create a hostile learning environment for students. It is discarding 11 book banning complaints, dismissing six pending ones and eliminating the agency’s book ban coordinator tasked with investigating school districts accused of censorship.

Craig Trainor, acting assistant secretary for civil rights, framed the moves as supporting local control and parental rights over the curriculum. The agency said that its attorneys found that books haven’t been censored but removed in concert with community members and “commonsense processes by which to evaluate and remove age-inappropriate materials.”

The Department of Education’s announcement led to immediate pushback — from the South Carolinians fighting to give students’ access to inclusive instructional materials to the freedom-of-expression advocates at organizations such as PEN America and the American Library Association (ALA).

PEN America said in a statement that it has documented nearly 16,000 instances of book bans nationwide since 2021. The prior year, President Donald Trump signed an executive order “to combat offensive and anti-American race and sex stereotyping and scapegoating” and the teaching of “divisive concepts” related to racism and sexism in the federal workforce or armed forces. That order led to most states introducing legislation that used similar language to restrict discussions and reading materials about race or sex in schools and other government-funded institutions.

Calling book banning a “hoax,” said Kasey Meehan, director of PEN America’s Freedom to Read program, “is alarming and dismissive of the students, educators, librarians and authors who have firsthand experiences of censorship happening within school libraries and classrooms.”

The amount of books banned over the past three years rivals the number of those banned during the McCarthy era of the 1950s, according to PEN America.

“This censorship organized by conservative groups predominantly targets books about race and racism by authors of color and also books on LGBTQ+ topics as well as those for older readers that have sexual references or discuss sexual violence,” Meehan said.

The ALA encouraged people concerned about book banning to attend library and school board meetings to support giving students access to a broad range of reading materials.

“Book bans are real,” the organization said in a statement. “Ask students who cannot access literary classics required for college or parents whose children can’t check out a book about gay penguins at their school library. Ask school librarians who have lost their jobs for protecting the freedom to read. While a parent has the right to guide their own children’s reading, their beliefs and prejudices should not dictate what another parent chooses for their own children.”

The ALA also gave Trump officials a warning: “The new administration is not above the U.S. Constitution.” But in a new executive order, Trump vowed to end what he described as “radical indoctrination” in K-12 schools by threatening to revoke federal funding from schools that teach about gender identity, racism, sexism and other forms of oppression. He also announced his intention to prioritize patriotic education, but it is unclear how his plans will affect public schools across the states.

In South Carolina, Mayes is one of many plaintiffs — including scholar and author Ibram X. Kendi, South Carolina Rep. Todd Rutherford and the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP — named in the federal civil rights lawsuit filed by Bailey Law Firm LLC and the Legal Defense Fund. They claim that the state has continually practiced censorship, largely through a budget provision barring state Department of Education funds from supporting the discussion of concepts related to race or sex. Several of the complainants are women, including educators and parents.

A spokesman for the South Carolina Department of Education called the lawsuit “meritless” in a statement to The 19th. The agency “will continue to seek meaningful opportunities to build bridges across divisions, honor the richness of our shared history, and teach it with integrity, all while ensuring full compliance with state law,” he said.

Plaintiff Mary Wood, a Chapin High School English teacher, faced a reprimand and calls for her firing after teaching Ta-Nehisi Coates’ memoir “Between the World and Me” in 2023. A Pulitzer Prize finalist, the book explores what it’s like to be a Black man and argues that systemic racism is woven into the fabric of American life. Two students in her class told school officials that the book made them feel ashamed of their whiteness, indicating that Wood had violated the budget provision prohibiting the use of curricula that make “an individual … feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his race or sex.”

Lexington-Richland School District Five officials ordered Wood to refrain from teaching the book, but her new principal eventually allowed her to teach it with some caveats, including offering an alternative viewpoint and emphasizing that students could opt out of the reading.

“A teacher's job is much more than providing rote education,” Wood said, explaining why she felt compelled to take part in the lawsuit against her state. “We are there to foster an environment where students can think critically, challenge ideas, engage in civil discourse and develop their curiosity. Their bright futures depend on exploring perspectives with which they are unfamiliar, seeing themselves in literature and receiving the truth of American and global history. Books offer the chance to create connections and develop empathy.”

But the censorship of books in her classroom caused her to “lose hope” as an educator, Woods said. Along with “Between the World and Me” and Kendi’s book, “Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism, and You,” coauthored by Jason Reynolds, South Carolina school districts have targeted books by queer Black authors such as George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue.” The state also used the budget provision to justify dropping AP African American Studies for high school students during the 2024-’25 school year.

A spokesman for the South Carolina Department of Education said that the state acknowledges that “African-American history is our shared history. South Carolina’s commitment to teach both the tragedies and triumphs of America’s journey remains unchanged, as outlined in our long-standing instructional standards.”

In 2015, a White gunman killed nine Black people at the historic Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C. The racially motivated mass shooting led to conversations about the state’s racial history and to officials voting to remove the Confederate flag from the State House. Critics of South Carolina’s budget provision say the regulation makes it difficult for educators today to lead similar discussions about the state’s divided past.

“This vague budget provision has been repeatedly used to censor instruction training or pedagogical tools on topics related to racial and gender inequality,” said Amber Koonce, assistant counsel at the Legal Defense Fund. “This case is about the unconstitutionality of a vague and discriminatory law. This case is about unlawful bias-driven censorship and the importance of students' right to receive information.”