It’s been a little over a year since Tram Gonzalez opened Color Wings Preschool in her home in Portland, Oregon.

Of the 15 children enrolled in her program, 10 attend for free, covered in full by Multnomah County’s Preschool for All initiative, which was passed by Portland voters in November 2020 to create universal free preschool for all 3- and 4-year-olds who want it.

This early into running her business, Gonzalez attributes her program’s robust enrollment and staffing to Preschool for All, which has provided her with both the startup grants to get established and reliable, adequate tuition reimbursements to operate with confidence.

“Preschool for All has opened up so many doors for families,” Gonzalez says, acknowledging that with her high tuition rates — which are necessary to cover operation costs, including payroll — her program likely wouldn’t be at full capacity this soon after opening without it. “It’s so expensive, like a mortgage.”

Shortly after its approval by voters, Preschool for All was paraded around policy and child development circles as an exemplar of what a universal preschool initiative could and should be. It was carefully devised, proponents said, to account for many of the details that often slip through the cracks in similar preschool proposals — impact on infant and toddler seats in the community, inadequate supply, workforce shortages — which can in turn have unintended consequences for the early childhood system in the community and lead to a failed initiative.

An article in The New York Times in November 2020 suggested the Multnomah County initiative could be a “national model” and a “blueprint” for the rest of the United States. Today, nearly halfway between its passage at the ballot box and its deadline to reach universality in 2030, Multnomah’s Preschool for All initiative is well underway. So how’s the rollout going?

Measuring Up

Successful universal preschool initiatives typically share a few common characteristics, says GG Weisenfeld, associate director of technical assistance at the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), where she works with cities and states to design and implement pre-K systems.

First, she says, there has to be a system in place to support the program, usually with a team of people who can champion the work and a strong leader who moves it forward.

Then you need funding — steady, substantial funding. Universal pre-K programs tend to have more staying power when they are paid for by a guaranteed funding stream, such as a tax initiative, versus pulling from a city budget, Weisenfeld notes. With the latter, preschool programs are vulnerable to changes in governance or an economic downturn. (Multnomah’s Preschool for All is funded by an income tax on high-earning residents.)

Next is an understanding of the needs, wants and realities of the community where the program will operate. This includes understanding the landscape of infant and toddler care, which is an even scarcer resource than preschool slots in virtually every part of America, as well as where and how to serve children with special needs. Part of this, Weisenfeld adds, is creating a preschool program that honors early childhood education’s mixed-delivery system, where families can choose among a range of educational settings, including center-based, home-based, faith-based and K-12 school environments.

Multnomah County’s preschool initiative has all of these ingredients baked into its design, which is key, Weisenfeld says.

Sometimes programs will have an ambitious design and then get sloppy when it comes to implementation. That is not what Weisenfeld has seen with Preschool for All.

“They did not cut corners,” she says. “They’re still pushing for high quality. They’re still pushing for equity. It’s impressive.”

A lot of universal preschool programs overlook assistant teachers and their pay, for example, Weisenfeld says. Not Multnomah. Some programs will include home-based providers but frame it as an inferior choice for families. That’s not the case here either.

They also collect and report data on their program rollout, Weisenfeld says, which she finds especially impressive.

So often, universal preschool programs start out as “grandiose plans” then get scaled back, and scaled back, and scaled back until it’s a kernel of its original form. “I don’t feel like this program has shrunk in that way. It’s stayed,” she says. “I think they’re going to be more successful than other places.”

Weisenfeld adds, of her colleagues at NIEER: “We share information about this program all the time. We say to city people, ‘Why don’t you talk to Multnomah County?’”

Slow and Steady Progress

The Preschool for All rollout is on track — even ahead of schedule, by several measures — according to Leslee Barnes, leader of the initiative and director of the county’s Preschool and Early Learning Division. Yet some Portlanders feel it’s moving too slowly, she acknowledges. Some local news coverage of the implementation has a tone of impatience.

In reality, Barnes says, it is going to take a while to get the system from where it was to where it needs to be. There is an enormous amount of building up and building out that has to be done.

“We’re doing a real intentional rollout,” Barnes says. “To the average consumer, or even politicians, they don’t really understand. ‘So what are you guys doing over there? Why doesn’t everybody who wants one have a preschool slot?’”

Slow and steady may not be a particularly satisfying approach to the voters who saw this initiative on the ballot, filled in the bubble signaling their approval, and expected a tuition-free universal preschool initiative to materialize right away. But it is what’s necessary to avoid the pitfalls of other programs that have tried and failed — and ironically, that same thoughtfulness is part of what attracted so much attention to Multnomah County’s proposal initially.

By expanding carefully, over the course of nearly a decade, Multnomah County is able to make good on its promises of protecting the supply of infant and toddler care in the community, of building out the supply of preschool slots to keep pace with program demands, and of improving the wages and benefits of the early childhood workforce so that it aligns with those of K-12 teachers in the area.

“We’ve met and exceeded all goals for preschool in every year we’ve been in existence,” Barnes says confidently.

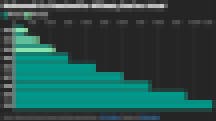

Preschool for All funds at least 2,225 preschool seats in the community, compared to its goal of 2,000 for this school year. About 800 of these seats are new to the county, meaning programs have opened or expanded their capacity since the rollout began; this includes the 10 seats in Gonzalez’s home-based program.

Next year, the goal is 3,000 seats by the end of the 2025-26 school year. But they’ll have 3,500 seats by the time the school year begins in September, with an additional 300 expected in January, according to Barnes and her team.

The goal is to create 11,000 Preschool for All slots by 2030. That should provide a seat for every 3- and 4-year-old in the county who is interested, leaders estimate. (There are about 13,900 children of that age in Multnomah County today.)

To help with all of the supply-building, Preschool for All awarded $9.5 million to 22 programs in 2023-24 — a mix of grants and loans. Some programs used those funds for renovations and repairs, while others built new facilities. In the current school year, the initiative has awarded $5.5 million to 25 different projects.

In addition to a startup grant Gonzalez received to help buy things like furniture, learning materials and kitchen supplies for her program, she also got one of the facilities grants from Preschool for All. She was able to use some of the $26,000 she received to build an obstacle course in the yard, paint her garage and start a garden that the kids will eventually harvest and eat from.

“The obstacle course is such a dream come true,” Gonzalez says. “I got to design something I really wanted, and it happened in real life. The kids love it.”

As a former early childhood teacher herself, she is grateful that the preschool initiative seeks to pay teachers a livable wage — and equips programs like hers with enough funding to make it possible.

The median wage for a preschool teacher in the Portland metro area, according to the Multnomah County Preschool and Early Learning Division, is a little under $18 an hour. For 2024-25, lead teachers with a bachelor degree who work at a program that participates in Preschool for All must earn a minimum of $29.42 an hour, with a goal of $39.23 an hour.

It’s the kind of wage increases that can be transformative for early childhood educators — and breathe life into a long-understaffed field.

Preschool teachers are also getting access to health insurance, retirement plans, paid time off and other benefits that are regular features of K-12 school district employment but can be hard to come by in early childhood.

“We know a lot of people leave to go work in the school districts because they have access to all these benefits and higher wages,” says Barnes. “We want [to have] a similar offering so it isn’t an excuse to jump ship. We have built-in increases to what we pay for slots annually.”

When Gonzalez was a lead teacher, she earned $20 an hour and thought she was doing alright, she says. Now, the minimum she can pay an assistant teacher is about $22 an hour. “It’s really nice what I can provide to staff, partnering with Preschool for All,” she says.

The administration of the program has also functioned really well, in Gonzalez’s experience. Every month, at the beginning of the month, the county sends a direct deposit to her bank account based on how many children she enrolls who participate in Preschool for All. It comes out to about $22,000 per child per year, she says, or a little over $1,800 a month. With that money, she pays her staff, covers operation costs and keeps what’s leftover as profit.

She may have opened Color Wings Preschool with or without Preschool for All, Gonzalez says. But she doubts she’d be as successful as she’s been without it.

Her five-year plan, she says, is to open a center-based preschool with three classrooms. Without Preschool for All, that would take her 10 years, easily.

“I have so many great things to say about it,” Gonzalez says. “I know the system isn’t perfect, but for me, on my end, it’s been a really great experience. I got to open my own program, which is a dream come true. They really helped make that happen.”