It doesn't much matter whether you cite Spiderman's Stan Lee or France's Voltaire for that deeply resonate quote: "With great power comes great responsibility." The line was echoing in the heads of high profile Udacity's founders over the past few days as news broke of the poor exam results of many students taking Udacity's classes offered in conjunction with San Jose State University.

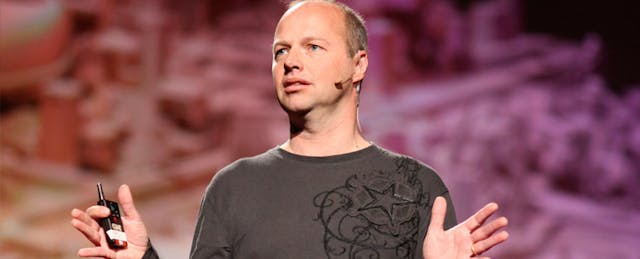

In a 1:1 interview with EdSurge, Udacity founder and CEO Sebastian Thrun said he is drawing many lessons from the experience--starting with how the classic semester schedule may work against students, the startling gaps in what students know and the logistical challenges of delivering online education.

None of those answers soften a harsh truth: many of the students who worked at these classes failed. Two SJSU professors describe the dismal passing rates (29%, 44% and 51%) in this piece in the San Jose Mercury News.

That outcome is disappointing, concedes Thrun, who has said many times that he hopes that Udacity can genuinely help students learn, regardless of their background. Although the program has "paused" until Udacity and the university can figure out how to best structure it, Thrun maintains that he's determined to bring Udacity back to SJSU.

So what happened? In January, Thrun and California Gov. Jerry Brown unveiled a high profile deal in which Udacity would provide course support for several remedial courses. Udacity would support three classes, created by professors at SJSU. Each class would have 100 students, half from SJSU and half from nearby community colleges and high schools. The students selected were not "typical" community college students: in many cases, they had already failed a remedial class or a college entrance exam. SJSU professors would design the course curriculum. Eventually the classes would cost $150 apiece. But at least on this iteration, foundations stepped in to cover that cost for students.

The professors creating the curriculum for the program didn't have much time; they were still writing curriculum when the courses began. "It was really hard on the faculty," Thrun says. "The amount of work they put in was admirable: they spent about 400 hours creating these courses." Whatever gaffs and bugs showed up in the curriculum was not a problem--just part of the organic back and forth of courses. "We had a whole bunch of clerical mistakes. In most cases we heard about it, and fixed it on the fly. It happens in the classroom as well," Thrun says. "Most of those will never show up again."

Then the unanticipated problems started to crop up. When the courses started, two of the three classes didn’t give students precise deadlines for assignments. "We communicated our expectations poorly," concedes Thrun. "We had two deadline-free courses. Especially in these classes, students fell behind. That was a mistake," Thrun declares.

The Udacity team began setting tougher deadlines and aggressively reaching out to students to help them make up for lost time. "We called every single student, sent out text messages and introduced deadlines," recalls Thrun. The effect was big: students caught up to their classes.

That push helped in another way: initially many students were unaware of the online tutors (who are real people) who were available online to help, 12 hours a day. But over the weeks, it became clear that the tutoring services were crucial. "The mentoring program was absolutely essential for every student's outcome," Thrun says.

Those tutors were so important because many students lacked even elementary-school-level mathematics knowledge, Thrun says. Among the frequently heard questions: How to divide two numbers? How can you subtract a bigger number from a smaller one? Tutors answered questions and continued to reach out to encourage students.

As the class progressed, Udacity also realized that many of the students simply couldn't get to a computer regularly enough. For some students, says Thrun, "there were none in the home, [and] even in school they couldn't get the hours needed to make progress. We had to work with the schools directly (to arrange for computer time for Udacity students.) It was actually a big deal." A June article in the Oakland Tribune outlined some of these challenges.

When students did get to the online programs, even navigating the computer systems could be daunting. One of the questions that tutors were frequently asked was how to do exponential notation on a computer. And although the curriculum was delivered on Udacity's platform, assessments were delivered via a separate learning management system used by SJSC. Worse: results on one system took about 48 hours to update on the other, says Thrun.

All that said, when students were surveyed, they said the biggest impediment to succeeding in the class was pacing: they just didn't have enough time. "Sal Khan has strong data that says in math in particular, a more flexible pacing is important for success," Thrun says. "He's been preaching go at your own pace and you can turn a C-level student to an A-level student." Thrun also pointed to Foothill College's "Math My Way" program which has been able to double its student-pass rates by giving students more time.

Thrun is proud of the number of students who completed the class--83% of the students finished, a dramatic increase from the usual, single-digit complete rates that MOOCs have seen. Yet the fact that the students continued to try makes the failed final exams even more poignant: "Yes, it's an enormous failure rate," he concedes. "I won't sleep."

The final analysis of the data from the courses isn't due back from the independent auditor for another two weeks. Once that data is available, Thrun says, he will develop an action plan for carrying on. "Let's improve infrastructure. And address the timing and pacing. I don't want to lock us into a semester frame if we shouldn't do this." Even so, he adds, there's "no doubt that we will carry on."