Few people negotiate as energetically to get their money's worth as a billionaire. And so it's fitting that a couple of billionaires are putting their money behind an effort that--at least in part--aims to help schools get full value for the dollars they spend on Internet bandwidth.

Today the EducationSuperHighway, a San Francisco-based nonprofit founded in January 2012 to help American K-12 schools get adequate high-speed Internet access for their students, got a huge endorsement from the philanthropic foundations set up by American billionaires Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates. All told, the EducationSuperHighway is receiving $9 million to support its work, including $3 million from Zuckerberg's Startup:Education and $2 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The group did not disclose what other "foundations and education entities" are contributing the additional $4 million in funding.

“This is very helpful,” says Richard Culatta, Director of the Office of Educational Technology in the U.S. Department of Education. “Obviously the federal government has a role” in bringing bandwidth to schools. “But there’s a really important role for a third party to play in monitoring what’s happening and in providing information,” he says. “We’re happy to see the EducationSuperHighway stepping up to that role.”

Case in point: over the past year, the EducationSuperHighway has completed 630,000 “speed tests,” or measures of just how much bandwidth actually reaches schools in over 30,000 schools. Increasingly the organization is also asking how much schools pay for that bandwidth.

The results, so far, have been unnerving.

“Adequate” bandwidth to support digital learning requires approximately 100 Megabits per second of connectivity per 1,000 students, according to the State Education Technology Directors Association (SETDA). Of those 30,000 schools, about 72% fall short of that bandwidth benchmark.

The prices they pay are even more troubling.

Evan Marwell, CEO of the EducationSuperHighway, reports that the top 25% of schools that have negotiated the best price for their bandwidth pay a bit more than $2 per megabit per month. The median school pays more than tenfold that price--about $25 per megabit per month to get Internet access to classrooms. And that means that some schools’ bills are more than $100 per megabits per month.

To shrink that gap, Marwell says his organization will use its new funding to support four projects:

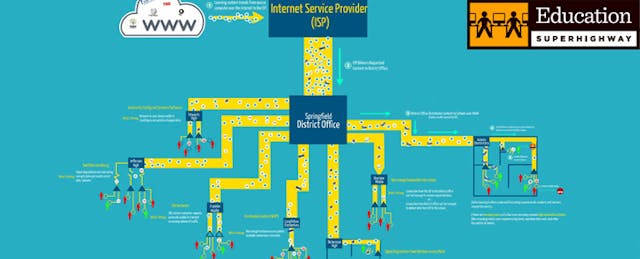

- Speed Tests: The program is still testing what bandwidth is available U.S. K-12 schools. Although anyone can run a bandwidth check on their local school, Marwell says that his team has had the most success when it has worked with local or state districts to complete the tests. To date, the EducationSuperHighway project has partnerships with about half of U.S. states and has completed its analysis of 18 or 19 states. It shares the data back with them.

- Technical Advice: The EducationSuperHighway is developing technical expertise, including a "Geek Squad" and "Network Cookbook" of reference designs to support schools upgrading their infrastructure to 100 Mbps.

- Procurement: The EducationSuperHighway intends to collect more data around bandwidth pricing and create an Internet Pricing Portal for sharing that data. One way to shrink the gap between what schools pay, Marwell notes, is to share pricing information more broadly and help districts and states form Regional Fiber Consortia to negotiate better prices.

- Policy: The EducationSuperHighway also hopes to help define how the Federal Communications Commission should spend its $2.4 billion “E-rate” funds.

The E-rate program was established in 1997 to help support technology in U.S. schools. This summer, the FCC invited comments on how to revise the E-rate program. “There’s almost nobody who thinks e-Rate reform is a bad idea,” Marwell says. But there are plenty of differences in how the money should be used--and even in how much money should be in play. Many education groups (including, for instance, ISTE) contend that the program needs at least $5 billion in funding. Fiscal conservative, by contrast, would like to see the program whittled down.

“We’re in the middle,” Marwell says. He argues E-rate funding should exclusively support broadband access (not cellular or television connectivity) and that schools will be able to cut better deals with telecom companies--ideally getting to an average cost of $2.50 per Mbps--when they have more information. At the same time, he also believes the program may need a “one-time” funding boost to ensure that schools have adequate fiber to get the bandwidth they need. “We were not originally thinking about connecting every school with fiber,” Marwell says. But after almost two years of analysis, his team concluded that giving all schools fiber is likely to be the most efficient way to solve current--and future--bandwidth needs.

“Everywhere we go, we’re seeing teachers who want to use the Internet but the network is the problem,” Marwell says. “I’m 100 percent convinced that as you fix the bandwidth problems, we’ll see schools’ usage explode.”