While the cool kids of education technology were in Austin at SXSWedu, the nerds clustered around each other in Scottsdale, AZ. The occasion? The annual Association of Test Publishers’ Innovations in Testing conference.

In case you think I use “nerd” in a pejorative way, ATP is a die-hard group of psychometricians, data scientists and assessment professionals whose efforts cover testing from grade school through the workplace. The influence of technology in the process was keenly felt among the estimated 1,054 attendees--said to be the most in the conference’s 15-year history.

One key area of change is toward so-called “innovative item types,” questions that eschew the traditional multiple-choice format to incorporate drag-and-drop matching or sequencing, clickable images, video and more. It’s a tech-propelled evolution that takes what can be dry text and turns it into something approaching a problem-solving simulation.

Think language learning exams that require responding to video conversations with native speakers. Imagine images of a leaky faucet that ask to identify where the problem might be, and what tools would be suitable. Envision audio of a human lung to help listeners diagnose what ails it.

Exhibitors ranging from Learnosity (offering embeddable assessments) to Breakthrough Technologies (offering TAO, an open-source testing platform) highlighted advances such as questions with video clips that have clickable “hot spots,” perhaps fittingly developed for a New York City firefighter’s exam.

Yet (spoiler alert) it seems many of these “innovative” question types now have been around for more than a decade, are actively in use in workplace and higher education exams, and are increasingly common to the point that the term for them has morphed into “technology-enhanced items.”

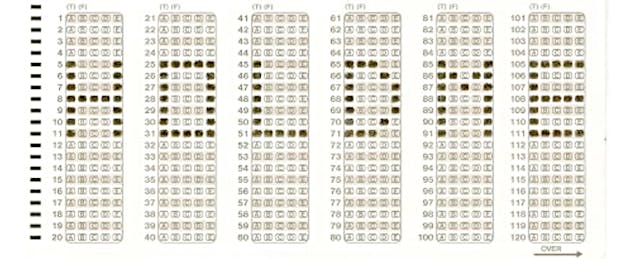

So why are so many K-12 tests still so Scantron?

Three factors kept coming up in my conference conversations, boiled down into the large pots of money, time and appropriateness.

Money

“Research costs may increase as you add these types of items,” notes Breakthrough’s Doug Wilson. Not only is there the cost of creating clear and unambiguous audio, video or static images (if a question isn’t just text), it likely takes more development brainpower to think through a question for which the scoring of an answer isn’t as straightforward as the choice of a single a, b, c or d. That means labor expense.

Another source of cost? Infrastructure. If a test delivers multimedia, every digital device used has to have the technical chops to properly represent it--and a school’s WiFi network bandwidth needs to be up to the task. That’s far from a sure bet, even today, as reports proliferate of technical failures messing with traditional text-based online tests.

Time

Adding innovative question types can extend a test’s length, as maneuvering drag-and-drop selections into proper order, or watching and responding to a short video or audio clip, simply may not be as fast a process as reading a question and clicking one of four answers. And parents and teachers are already up in arms about the amount of time required testing takes away from instruction (not to mention test prep).

Take what appears to be a single question with equipment animations and clickable hot spots. While it may actually measure more of what a student knows about, say, a science lab process, it probably would encounter pushback if it extended total testing time. For good or ill, testing time today is a zero-sum game.

Appropriateness

In a comprehensive session on the subject, psychometrician Adrienne Cadle of Professional Testing Inc. flatly stated, "You shouldn't put innovative items in a test just because they're fun, or just because your software allows you to." Cool does not automatically equate to useful. A key criteria in choosing what kind of question to use, added Cynthia Parshall of CBT Measurement, should be that “It enables you to measure something more, or measure something better.”

In other words, sometimes a multiple choice question really is just a multiple choice question.

Even the most tech-savvy students of all ages may also be stumped by one unexpected consequence of bubble-sheet domination: over-familiarity. Parshall discovered that test takers faced with, for example, a type of innovative test question that required several responses “choose [only] one answer and go on.” The cause? “We've spent years training them for multiple choice.”

Any lack of familiarity with innovative items will itself soon be tested in K-12 education. Both Common Core assessment consortia plan to include some technology-enhanced items in their forthcoming math and English language arts tests. While these may not have all the bells and whistles of clickable HD video, they will take advantage of digital technology and attempt to improve and extend what’s measured.

Brandt Redd, CTO of Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, says constructed-response items that “require a student to compose something” (rather than just selecting from a pre-determined set of answers) will include entering mathematical expressions and plotting points. Other questions “involve drag-and-drop manipulations (such as ordering items in a list) or marking intersecting rows and columns in a grid as a form of matching.”

But concerns about time, cost, infrastructure and simple measurement appropriateness may continue to be reasons why that for many school uses, multiple choice rules. And why most tests can’t have the cool toys--even if they prove to be useful.