Virtual Nerd, a well-regarded math technology company, is struggling with the kind of news that can cause a startup to come unglued: Its principle funder is backing away.

Last weekend, the company let go all but three employees: co-founders Josh Salcman and Leo Shmuylovich (both vice-presidents) and president Mary Louise Helbig. Rather than shut down the site and leave teachers and students in the lurch, the team plans to continue operations at least until the conclusion of the school year. At the same time, the trio is looking for additional funding--or a potential buyer for its unique interactive video technology. At least one significant funder has been Quantum Ventures of Michigan.

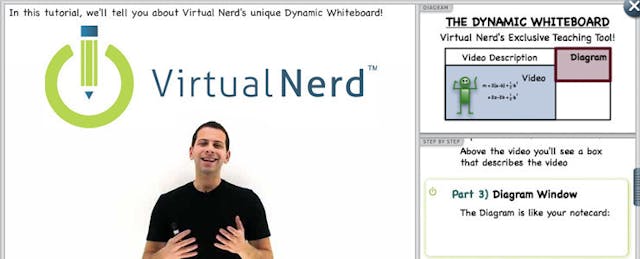

Virtual Nerd has built "interactive white board," software used to teach math from grades 6 through algebra 2. (The company says it has applied for a patent for the work.) Rather than just broadcast a lecture or information, the virtual whiteboard lets students dive into questions and links throughout the material.

Virtual Nerd's news will dismay its fans as well as educators who are nervous about betting heavily on startup technologies that could vanish if the young teams building them stumble in the process of growing the company. The past two years have seen an upwelling of edtech startups, fueled by entrepreneurial zeal, diet sodas and skimpy budgets. Not all will make it. Watching this Darwinistic culling of the herd, however, is about as pretty as watching cheetahs take down a gazelle on the savannah.

Since the days of the epic battle between competing video formats (VHS versus Beta), industry players recognize that startups need a magical combination of factors to survive.

A strong product--ideally one that serves a real need and, in the case of education, is built on research--is literally the seed kernel of a company. Without it, there is no company. The second step is proving the team functions well together and can deliver what's promised. Then come the business questions--the care and feeding of the organization. Among the business choices that will influence whether a startup will survive are:

- What's the company's business model? (Does it seem on a path toward generating sustainable revenue?)

- Will it be able to generate revenue? What's the "sales cycle" of the industry? How quickly can the company close a sale?

- How quickly it is spending money? What's its "burn" rate? How many staff does the company have? How expensive are they? How is it spending its cash?

We've heard of one young company that closed shop soon after raising $100K because a co-founder demanded a six-figure yearly income. (C'mon, do the math!) Far more typical, however, is that seed funding gives a startup a chance to demonstrate that it has a plan for growing both customers and ultimately revenue. But if there's too big a rift between when a company's investors think it should be generating revenue and when it actually closes sales, disaster can follow.

Virtual Nerd may be going through just that kind of near-death experience. The company got its start based on a decade of experience in tutoring by one of its two co-founders. The duo aimed to support "non-linear" learning or exploration in video. They established a value statement crucial to educators: "Quality matters in every aspect of every experience, so we must not cut corners." And they won praise for their work, including recognition from the SIIA and Maths Insider.

Sales to school districts, however, have clearly lagged behind what investors had hoped to see in spite of usage by the likes of NewClassrooms, Florida's Brevard district and California's San Jose Unified district. That most districts take more than a year to make a sales decision--and that so many sales are still influenced by the relationships between sales staff and those doing the buying--can potentially throttle small companies.

On the other hand, no school district wants to be the last buyer from a limping company.

"The education industry is in a state of flux with regard to whether it's buying technology first or content that will run on that technology [infrastructure]," Helbig notes.

Where the technology--and the company--goes from here is now equally in flux.