Can game-based learning help nontraditional students improve outcomes? That’s the central question behind a report released today by Muzzy Lane Software, a Newbury, Mass.-based game development platform.

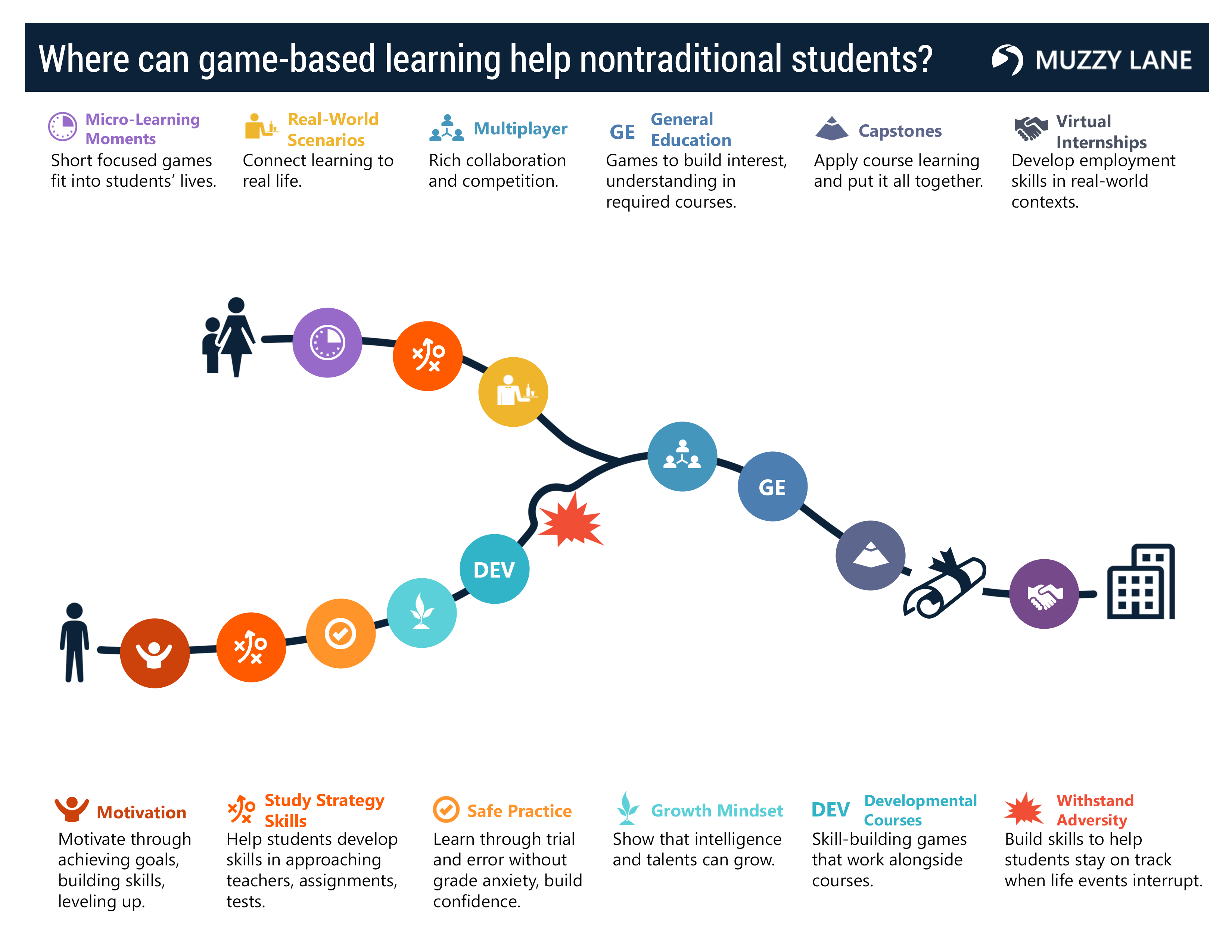

Game-based experiences like role-playing scenarios and puzzles can let students test competencies in a safe environment. The new report shows the potential for these learners to benefit from modular, game-based approaches that fit within their lives and their instructors’ workflows.

“We hope that this [research] leads to educators and curriculum designers and game-makers thinking about approaches to games that can overcome hurdles of cost and fit that have been holding things back,” says Bert Snow, principal investigator and vice president of design at Muzzy Lane. The company pivoted its own approach to game design based on two key lessons from the study: educators don’t want all-encompassing game-based courses; and they see opportunity for affordable, flexible “learning moments” from games if tools are easy to implement.

The study, “The Potential for Game-based Learning to Improve Outcomes for Nontraditional Students,” is based on research funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and includes insights from a survey of 1,700 students, 11 in-person focus groups and interviews with teachers and school leaders. Educators said games could be especially helpful in several areas: auto-assessing whether students can apply what they’ve learned, building employment competencies and improving study skills.

Who Are Nontraditional Learners?

While the definitions of nontraditional student varies, Muzzy Lane characterizes them as learners who meet two of the following criteria: returning to school after pausing their education, balancing education with work and family responsibilities, lower-income, English as a second language learners, or the first members of their families to attend college.

Nontraditional students, who make up the majority of post-secondary learners, cram in study sessions during the work commute or after they put the kids to sleep. The in-person and online classes they take often lack opportunities to practice the employment skills they need. Many of these adult learners want to know that what they’re learning has concrete applications in the real world. “You are not going to learn the stuff you need to survive in nursing school in [my school’s] online classes,” one pre-nursing student told Muzzy Lane researchers. “A lab practical needs to have practice in it.”

Muzzy Lane’s observations led the company to challenge some of its assumptions about the efficacy of game-based learning. While it had previously approached GBL as a standalone solution, it learned that games are only one part of a holistic--and flexible--curriculum. “World of Warcraft is wonderful, but a game that’s big and all-encompassing isn’t going to fit in with the life of a student who has limited time,” Snow says. “We really see relevance for GBL in pure practice, being able to apply what you’re learning.” Role-playing games, for example, set the context for nursing students to try interacting with patients in a safe environment.

Overcoming Challenges

Even if instructors wanted to implement game scenarios into their coursework, they’ve faced major hurdles. Those challenges to adoption include the often prohibitive cost to develop and maintain custom game-based coursework and finding ways to fit games in with existing curriculum.

Muzzy Lane has reassessed its own approach to game design based on feedback from students and teachers. Instead of building full, game-enabled courses, the company is focusing on modular, flexible GBL experiences that address specific needs. It released an authoring solution that let educators develop and deploy dynamic game-based content. Snow says that Muzzy Lane has started working directly with several schools that serve nontraditional students and that the company expects to be collaborating with many more soon.