At the SXSWedu workshop “Enhancing Learning with Virtual and Augmented Reality,” held on Monday, Mar. 7, roughly 20 people spent most of the time waiting in line to try one of the three devices, according to Maya Georgieva. The event made her nervous that there wouldn’t be enough devices at her own talk, “Learning Through Virtual Reality Experiences,” presented with her co-founder, Emory Craig. Together, they have created Digital Bodies, an outlet that covers how wearable tech, virtual reality included, will influence teaching and learning.

Fast forward to their session on Wednesday, where they began by profiling the virtual reality device industry and its upcoming offerings—including Oculus, the Homido Mini, Meta Glass, Microsoft’s Hololens, the Mattel Viewmaster, Magic Leap, Google Cardboard, Samsung Gear VR—and discussing how most of the high-profile tools are currently in the development stage. Few devices are out on the market now, but virtually every major tech company and even major film studios like Lucasfilm have announced a device that will enter the space in 2016. There is even a virtual reality theme park in Utah and a theater in Amsterdam. The virtual world is about to get crowded.

The speakers were optimistic. “It’s now really about experiences. It’s no longer about content,” Georgieva said. “It’s no longer about visual resources on a device. It’s about worlds.”

Craig then quoted Chris Milk, CEO of virtual reality app Vrse, who famously dubbed virtual reality the “last medium”:

“Ultimately, what we’re talking about is a medium that disappears, because there is no rectangle on the wall,” Milk told Re/code, “and there is no page you’re holding in your hand. It feels like real life.”

Milk also offered an opinion on the proliferation of press about virtual reality with comparatively little content and few devices: “I prefer making stuff to talking about how I made the stuff,” he said. “Right now, there’s a lot of people using the technology and the format to impress people. There’s a certain reliance on the ‘wow’ factor out there. If people are going to engage with the technology on a longer scale, they’re going to need deeper, more affecting, more human stories to engage with.”

Despite a lack of compelling content, interest continues to rise, and not just in the press. Craig estimated that there are 100 centers studying virtual and augmented reality at universities across the US. Half of them opened in 2015. Investors are banging on the doors of companies like Magic Leap, which won a $900 million investment from Alibaba’s Jack Ma at a $5 billion valuation—without a product for sale. According to a recent TES Global survey, 10 percent of teachers would most like to see virtual or augmented reality headsets enter the classroom, a twofold increase from last year.

The promise of the medium piqued educators at SXSWedu 2016. Most at the workshop were optimistic about the virtual reality’s potential, and as they tried different viewers and content during Craig and Georgieva’s workshop, they offered some insights.

“I would definitely use it for virtual field trips, both in higher and elementary education,” said Jeannine Perry, Dean of Longwood University’s College of Graduate and Professional Studies. “It’s like watching science fiction unfold. I’m 53, so I’m pre-cell phones, and computers were only appearing in my teens, so this is amazing.”

Laura Nooney, a game designer attending on behalf of the community media center Brookline Interactive Group, compared virtual reality’s upcoming expansion to the transition from mouse-based games to touch screens. The possible removal of technological barriers to young children, in particular, excited her.

Nooney believed the logistical problems that users currently face—the rough feeling and poor resolution of Google Cardboard bothered her—would be solved before long. The next and more important issue, she said, would be making the medium both relevant and educational.

“Virtual reality will be a kinesthetic, immersive experience for students. They’ll learn things in a visceral way,” she said. “I want to know how that boosted engagement will be coupled with good teaching and scaffolded by learning science.”

Much of the press and several of the SXSWedu panels on virtual reality talked excitedly about where the medium and technology will be, rather than where it currently is. A substantial conversation can’t subsist on predictions alone, though. One session focused solely on the “now”: The British Museum offered insights from its pilot virtual reality program, where it created a virtual Bronze Age roundhouse populated with relics from the era. Lizzie Edwards, Education Manager of the Samsung Digital Discovery Center in the British Museum, said that attendance increased fourfold from the normal 300 to 1200 people during the weekend the museum tested its virtual reality offerings. The sizable audience flocking to her 15-minute talk reflected the draw of the program.

Edwards’ team offered virtual reality headsets, in an interactive dome and on tablets. (Students 13 and under were not allowed to use the headsets because of British health and safety codes.) Museum staff facilitated participants’ interactions on a one-to-one basis, which Edwards said kept the flow of visitors moving at a reasonable pace for everyone to see the roundhouse.

Why a Bronze Age roundhouse? Edwards said the project came about because of shifts in the United Kingdom’s national curriculum introduced in 2013. Teachers in the UK must now instruct students on changes in Britain from the Stone Age to the Iron Age, which may include, according to the British Department of Education, “Bronze Age religion, technology and travel.” Edwards said teachers immediately began complaining that few educational materials existed to help students visualize and understand Bronze Age environments.

The museum is still determining how to integrate the experience into its regular offerings. Edwards asked, “Is it a fad or a lasting means of object investigation?” Edwards claimed she won’t advertise when the museum will offer virtual reality again because she doesn’t want it to become a gimmick. She wants museum-goers in her Discovery Center for the Bronze Age, not the virtual reality.

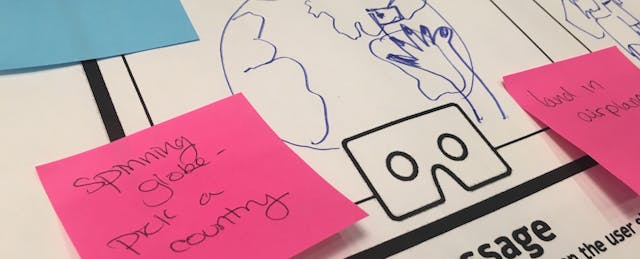

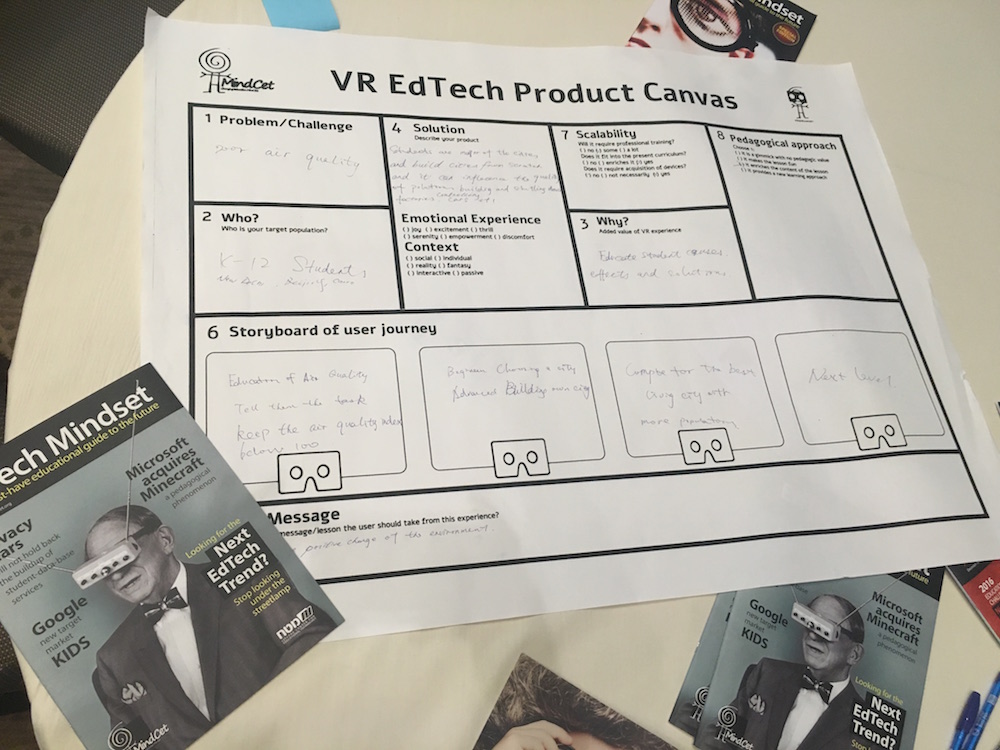

Back on the podium with Digital Bodies, Georgieva had enough devices for her participants, roughly two per table of six, but her observation about the ill-prepared workshop that preceded hers may prove telling as virtual reality attempts to expand.

“We’re all very excited for VR to evolve,” she said. “It’s very experiential, but not very many people get to experience it.”

Her remarks beg the question: Are virtual reality and storytelling as a whole “now really about experiences,” as Emory Craig said, or must we still wait for the technology and the content “to evolve” and catch up with expectations, as Georgieva said?