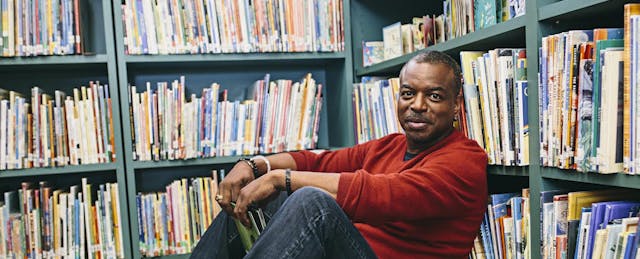

He has touched millions of lives for years. LeVar Burton burst into the public arena with his powerful performance of the African captive, Kunta Kinte, in “Roots.” He was only 20 years old then but helped raise the consciousness of the nation. A few years later, he became the geeky, blind engineer, Lt. Commander Geordi La Forge on “Star Trek: The Next Generation.” And then began his most ambitious effort: Hosting and producing “Reading Rainbow,” a television program that delivered books and a love of learning to children via television. Some 155 episodes—and 26 years—later, when PBS lost funding to continue “Reading Rainbow,” Burton acquired the assets and headed up a Kickstarter campaign to transform Reading Rainbow to an online virtual library. Skybrary School now has more than 1,000 online books, more than 260 videos and has milllions of fans among parents, teachers and students.

Last week at the Lead3 Symposium in Redondo Beach, CA, sponsored by the Association of California School Administrators (ACSA), CUE, and the Technology Information Center for Administrative Leadership (TICAL), I had the opportunity to interview Burton.

In a powerful and emotional conversation, he discussed the power of storytelling, the power of aspiration and the power of love. All of these, he says, are fundamental ingredients in personalized learning.

EdSurge: You’re famous for your love of literacy. What sparked that love affair?

Burton: My mother was an English teacher. Literacy was mandatory in Erma Gene Christian’s household. I like to say that you either read a book or she would beat you with it.

That meant “War & Peace” made a big impact?

Yes. My mom is an avid reader herself and is always reading two, or sometimes three or four books. So I grew up in a household where reading was like breathing. I learned at a very early age that reading was an essential part of the human experience. And my mother didn’t just read to me—she read in front of me. That modeling was really critical to my understanding of the role that literature played.

You studied to be a priest. And then there was a moment, a moment when you discovered the power of acting. What happened—and what did the experience mean to you?

I was in the seminary in California for four years. It was run by the Salvatorian Society of the Divine Savior. It is an order primarily out of Milwaukee—so they liked their cheese and they loved their beer. When I was a sophomore at St. Pius, we put on T.S. Eliot’s play, “Murder in the Cathedral,” and I won the role of Archbishop Thomas Beckett. We had the opportunity to do the play in the cathedral in downtown Sacramento. At beginning of the second act, I started Tom’s sermon by saying, “In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti.” And all the people in the audience made the sign of the cross. That’s when I thought, ‘Wow. This is the power of performance.’ And that’s when my attention began to shift away from the clergy and theology to story telling and performing arts.

The power of storytelling runs pretty deep.

It’s clear to me, looking back on the 60 years of my life, that I was destined from the very beginning to be involved in storytelling and to become a storyteller in as many different facets and fashions as possible.

And then you took an epic trip to New York City, to see one of your heroes, Ben Vereen. Tell us about that time.

Four of us students took a summer road trip to New York City with a priest who taught us all to drive and smoke. The main purpose of the trip for me was to get the Imperial Theater and see Ben Vereen in “Pippin.” I idolized him. I bought a box seat. And I went by myself. No one else wanted to go to see this musical on Broadway. But that was my thing. Then I waited two hours after the show at the backdoor. And Ben Vereen came out and I got my program signed. And I said, ‘Mr. Vereen, my name is LeVar Burton and I really hope to work with you one day.’

That was kind of amazing thing for a student to say. How did you have the courage to say that?

I didn’t know the difference between confidence and BS.

Four years later, Ben Vereen and I were in “Roots” together. And I called my mom in Sacramento and had her send me a copy of the Polaroid. Remember Polaroid? That Polaroid snapshot that I had of him and I, that in the alley backstage. I showed it to him. And of course he didn’t remember. But I had the proof! I had the photograph. That was an incredibly validating moment for me.

And there was another pivotal moment in your friendship, one that you don’t typically share but I will: A number of few years later, after Ben Vereen had a serious illness and had been out of work, you helped bring him back to the work of performance by inviting him to be on “Star Trek: The Next Generation.”

I invited him to come and play my father on “Star Trek.” That was also a dream come true for me—to be of real value at a time in my hero’s life when he needed help. I will always be grateful that he gave me the opportunity to give back, as he had given me so much when I was growing up.

Through this conversation you’re going to hear the power of storytelling, the power of aspiration, the power of love. It’s not an accident that we’re having this conversation at an education conference. Because in a deep way, these are the building blocks of true personalized learning.

Now let’s talk about “Star Trek”! So I confess: I’ve been a Trekkie my whole life. But why did you decide to do that? And what was the meaning of that experience for you?

My whole family has been Star Trek fans going back to the original series. Gene Roddenberry’s vision of the future meant an enormous amount to me.

I’m a science fiction fan, that’s my body of literature. When I’m reading for pleasure, that’s my jam. But it was exciting and fairly uncommon for me to encounter heroes in the pages of the science fiction novels that I read that looked like me.

Gene Roddenberry’s version of the future was different. Seeing Nichelle Nichols [the African American actress who played Lt. Uhura] on the bridge of the original Enterprise meant the world to me. As a storyteller, Roddenberry was saying: ‘When the future comes, there’s a place for you.’ It was a representation of the future that I could project myself into.

I learned at a very early age how important it is for people to see themselves reflected in the popular culture. And I saw that when one does not see themselves represented in the popular culture, real damage—subtle but powerful damage—can be done especially to a developing identity. So “Star Trek” has always been a part of me.

And what Nichelle Nichols meant to you, as an African American—you then extended to people with disabilities, when you joined the crew of “Next Generation.”

Yes. Being able to represent for people who have physical challenges the way that Nichelle represented for people of color was again, was an opportunity, an act, that informed who I am.

And tell the truth: That visor. Did it hurt?

Yes. It didn’t hurt until I had it on for more than 45 minutes. Which is why when we started the movies I insisted on taking that technology and making it a smaller device.

It was an upgrade.

It was a great upgrade for me. And it was conditional: I wasn’t interested in wearing the visor any longer. After seven years, I had had enough.

Do you have a favorite “Star Trek” moment?

My favorite “Star Trek” moment didn’t happen on the set. When I got married in October 1992, my best man was Brent Spiner, who played Data, and my groomsmen were Michael Dorn (Worf), Jonathan Frakes…and Patrick Stewart. We are very much a family. So my wedding photo is pretty amazing.

You worked on 155 episodes of “Reading Rainbow.” What drew you to that project? There was a bit of controversy in the beginning, wasn’t there? To people who thought that television was just rotting kids’ brains, the idea of putting books on TV was a bit weird. So why do it?

“Roots.” “Roots” showed me the power of the medium. In eight nights of television, I experienced how we transformed how we talked about slavery in America. It was eight consecutive nights that changed this nation, and changed how we refer to our very conflicted feelings about our very controversial past. That was done through stories. Television had the power to not simply entertain but to deliver so much more: Consciousness. Community. When “Roots” aired, its audience grew almost exponentially every night. By that eight and final night of “Roots,” almost the entire country was tuned into a singular event. Simultaneously. That will never happen again because we consume our content in a much more fractured way. “Roots” brought this nation together, in front of that cold fire of television.

We watched together, as a nation, in our individual living rooms. It was a communal experience. And it had the power to change minds. The power to change and shape consciousness.

“Roots” had proven to me that there was enormous opportunity. So when the idea was presented to me to use this powerful media to create linkages between emerging readers and the written word to combat the summer loss phenomena, I was like, ‘Yeah! Let’s do that.’

So what were some of the goals you had with “Reading Rainbow”?

To share stories. Points of view. We wanted to reflect the world in a manner similar to what these kids are experiencing as they are growing up. We didn’t want to shy away from some of the difficulties that are involved in growing up.

One of the very first episodes of “Reading Rainbow” was a book by Barbara Shook Hazen called “Tight Times,” a story about a kid whose father lost his job. We made a supreme and conscious effort on Reading Rainbow not just to meet the audience where they were. We wanted to take them places—to physical places and expose them to different activities and destinations. And we wanted to expose them to a more holistic way of looking at the world. To interacting with the world.

Do you have a favorite “Reading Rainbow” episode?

Ah, so many of them are triggers for so many great memories. I learned how to fly an airplane. I learned how to dive when we did something on the coral reefs. We stood on the summit of Kilauea, while a volcano erupted over my shoulder. Every single one of those books represents an experience I had and a person I met. Somebody shared their story with us. And we, in turn, have an opportunity to share that story with our audience. So it’s hard to pick a favorite.

But there was one particularly special episode we did, based on a book called Amazing Grace. Amazing Grace is about a young girl who wants to play Peter Pan in the school play. Her classmates tell her she can’t—first because she’s a girl and second, because she’s black. And Grace proves everybody wrong because Grace has the power of imagination

For that episode, Whoopi Goldberg joined us and shared her story with the audience. Whoopi said she saw herself as “Grace” because all her life, she had people who told her she couldn’t do this or that. All of her life. And Whoopi maintained her belief in herself and her destiny and proved everyone wrong—because she believed. Because she could imagine something different.

Doing that episode was a very proud day for us because that’s a lesson that every child needs to hear.

And you have had the tenacity to believe and imagine, too—including having the courage and belief to transform “Reading Rainbow” when it was going to be cancelled and turn it into a startup. That might have seemed a little crazy. What gave you that courage?

I’d say I didn’t know the difference between courage and foolhardiness.

I did not when we began to reinvent “Reading Rainbow,” not to bring it back to TV but deliver it via the web, I did not know how hard the journey would be. Neither did I know how delicate it is to take a chance like that with a stellar, platinum brand, and to reintroduce it to a whole other generation. It could have gone horribly wrong. So many things could have gone wrong.

Oh, tell us one.

Well, some of these wounds are self-inflicted.

Yes. I know those scars. I’m running a startup too. Want to see mine?

Oh, there are so many. But what got us through was the team. I work with a phenomenal group of people who are supremely dedicated to this mission and are at this company because they want to make a difference in the lives of children. At the end of the day, there isn’t a person in the company today that doesn’t feel that way.

To have people around you who are of a like mind and consciousness, and to know we’re all working toward the same goal of genuinely making a difference in the lives of children makes all the difference. That’s what gets us up in the morning.

One of the strengths of moving to the web is that it is giving you an opportunity to bridge what happens in the school with what happens at home. How does that happen?

One of the unexpected consequences of “Reading Rainbow” having been on TV for so long was that we built up enough episodes in our library to be available year round. “Reading Rainbow” became the most-used television resource in our nation’s classrooms. That connection between teachers and “Reading Rainbow” was something that I didn’t expect.

We launched a consumer app. And then we began getting all this empirical data and anecdotal evidence from teachers who were using that consumer version in their classrooms. It wasn’t built for that—but they were rigging the system and putting 35 kids on it. So part of the reason to do the Kickstarter campaign was to give teachers a tool that was designed specifically for them—something that included lesson plans, an ability to roster 35 kids and all the bells and whistles that make a difference in teachers’ lives.

At the same time, when a classroom uses the app, which we call Skybrary School, we make the library of books and videos available to families to use at home.

A question about politics. You went to parochial schools. You said that mattered to your mother. So where do you come down on the current administration’s enthusiasm for vouchers?

The way the current administration seems to be positioning vouchers seems to be setting us up to abuse that system horribly. It could mean that those most in need get the least amount of attention from that system. And that would be a real shame.

Vouchers, in an environment where vouchers work, offer choice. To parents. To families. I wouldn’t be the person I am if my mother hadn’t found a way to make sure I attended a private school. It was important to her. And I believe that is a luxury that shouldn’t be reserved for a certain class, a certain strata of society.

But to use vouchers to suck up all the resources and still leave those at the bottom of the ladder behind—that’s just purely wrong. It’s just flat wrong.

You’re planning to tour some schools. Why? What do you want to learn?

I want to get in the classroom next year and I want to talk to teachers. I want to observe how they’re utilizing our product, Skybrary School. I want to see what their challenges are. I want to hear from them about their hopes and aspirations and understand where that gap is—that gap between what they want for their kids and what they are able to do for their kids. I want to use, as best as I’m able, the agency of my celebrity to help bridge that gap.

Another swelling concern is education is social-emotional learning. And you had a friend and mentor, Mr. Fred Rogers, who inspired you. I understand that you had Mr. Rogers in mind when you wrote a children’s book a couple of years ago, called The Rhino Who Swallowed A Storm. It’s a powerful story because it acknowledges the sadness that children can feel. It doesn’t pretend the emotions don’t exist. It talks about loss—but also about the process of recovery. How did that come about?

We were with “Reading Rainbow” cameras a few years back and shooting in Central Park. And we heard the news of another one of those situations where somebody had gone into public space with an automatic weapons and killed people. It had come on the heels of a couple of natural disasters, including a hurricane.

And I realized that Fred, were he still here, would have addressed, in an age appropriate way, with children how to handle growing up in a world where these tragedies continue to take place. But Fred wasn’t here. And I didn’t see anyone stepping into the space and talking to kids about how to process and how to recover from tragedy. I talked about it with our company, and our CEO, Sangita Patel marshaled the resources to make it happen. Rhino was her baby. We are all enormously proud of it.

So what’s next?

I don’t know. And that is absolutely appropriate. I have no idea what the next chapter is. But my goal is to be part of the process. To stay engaged, to keep helping, and to be passionate about being in the game. That’s my goal in life. Whether in education or in show business, I want to be in the game. Be in the game. You cannot change the rules from the sidelines.

Today we’re talking to a community of educators, people who are sometimes up against some powerful forces. What’s your message to this community?

Stay with it. Stay. Alive. Awake. Alert. Stay enthusiastic about what you do. Stay joyful. I don’t know how you do it. My mother was an English teacher. Teaching education—my sister is in education, my son, as are two nieces. If you are a Burton, you are in the education business. I’m in the family business from this other branch, called edutainment. But I have so much love and respect for what you do. And I have the sense that you are—and perhaps feel—like you are under assault. Under assault in the service of doing that which you love to do.

This country, this culture, does not value the contributions that you make on a daily basis. We have spent—and apparently are going to continue to spend—far too much money on war and the machineries of war. We are leaving our children in the dust as a consequence. And that, to me, is not okay.

And so I would encourage you to stay in the game. Stay in the room. In spite of the challenges. In spite of the hardships. In spite of the obstacles. You are valued. There are people who see. I see. That’s my message to you. I see you.