In just over a decade, 21 independent education companies have raised more than $2.9 billion in funding and are shaping the way education is evolving for students from grade school to higher ed. Collectively, 119 directors serve on the boards of these privately-held companies. Only eight are women. Even fewer are women of color.

The scarcity of female directors in edtech is a striking contrast to the diversity that exists in the sector's day-to-day leadership. As much as one-third of edtech companies started during that time have a female CEO or founder.

While corporate boards seldom draw the attention of end users, they set the strategic path and hold the power to make fundamental decisions about the companies. So without underrepresented voices added to corporate decision-making and product direction, companies can struggle to understand, let alone serve diverse populations and learners.

New Tools, Old Challenges

The past 10 years have seen an explosion in the number of companies that serve schools. Some 25 years ago, three textbook companies heavily dominated the business of providing materials to public K through 12 schools. By contrast, EdSurge estimates that more than 2,500 companies and organizations have popped up since then, serving up a dizzying array of products to schools.

Yet while representation of women founders might be better in edtech than the mainstream startup community, diversity has an even longer way to go when it comes to the boardroom.Edtech observers have noted that a significant number of those companies have been started by women. At this year’s ASU+GSV education technology conference, organizers shared data that showed about 34 percent of nearly 180 companies presenting at the event had a woman founder or CEO. That’s double the share of women-led startups nationwide, which amounts to only 17 percent. (Many more small businesses are started by women; these are companies that raise outside funding.)

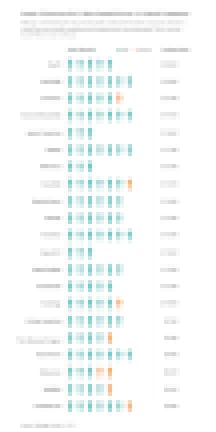

EdSurge looked at 21 independent companies, all still privately held, that have raised the most venture capital funding in the last dozen years and found that less than half of these companies have a single female board director. In total, women make up just under 7 percent of board members. Only one company on the list has a female CEO: Ayah Bdeir, founder and board chair for coding kit company, LittleBits, which has raised $62 million.

See our full list of companies and board members here.

Experts agree that simply adding more women onto boards is not enough to solve the deeply embedded issues of gender inequity and harassment that are pervasive in the technology industry.

“[Adding women to boards] can’t be a charity case,” says Deborah Quazzo, a co-founder and managing partner at GSV Acceleration. “There has to be real support and accountability on both ends for people trying to improve the pipeline and those coming through it.”

Quazzo is a voting board member on three edtech startups and an observer on the boards of two others. She is also the only woman on each of the boards where she participates.

Another female venture capitalist, Melissa Guzzy, recently wrote about how she too has rarely served on a board with other women during her career as a co-founder of Arbor Ventures, which invests in early stage tech companies. Out of the 18 corporate boards she has ever sat on, only one company has had a board with another woman on it.

“I have been [investing] for 17 years and we still haven't made substantial progress,” says Guzzy.

Quazzo attributes the gap to the scarcity of women and minorities investing and working at senior levels in VC firms. A recent study by Deloitte found that out of 2,500 venture capital employees, almost half (45 percent) are women who largely occupy administrative or communications roles. However, only 11 percent of investment partners—such as a managing or general partner—across the industry are women.

“This goes back to a bigger issue of how, in venture capitalism, there isn’t a broader embrace of the idea that diverse sets of people should be involved in investment committees,” says Quazzo.

Sabari Raja, co-founder of Nepris, which virtually connects students and teachers to industry experts, says that the investors she has met as she has been raising her first round are interested in companies that can make an impact in the classroom—as well as generate a profit. And that points to the need for more female directors, she adds.

“If, as a company, your goal is to make an impact in education, then you need representation on your leadership that can relate to the population you are trying to impact,” says Raja. “Otherwise we’re just saying, ‘We think this is what kids need,’ and we’re not always in the right position to make those decisions.”

Shauntel Poulson, a general partner at edtech investment firm Reach Capital, serves on three boards as a voting or observing member. Only one—Schoolzilla, a K-12 data analytics platform—has another woman and that is CEO and founder, Lynzi Ziegenhagen. Poulson is also the only person of color on all of the boards she sits on.

Women made up 76 percent of public school teachers from 2011-12, according to the National Center for Education Statistics 2016 report. That makes the board statistics problematic for users, she explains, because directors make governing and legal decisions that influence what students and teachers use to learn.

“[The board] influences product design and priorities,” says Poulson. “It can actually impact student achievement.”

The issue goes beyond the simple lack of women in the investing space and is often compounded by the corporate roles women are offered in the first place. Poulson said has seen instances where women investors may be more likely to be given observing board seats, which allows them to attend board meetings and weigh in but not vote on company decisions.It also drives business choices around customer needs. “Is it really right to have a group of white men who tend to skew older making decision for people different from them?” says Malli Gero, a co-founder and president of 2020 Women on Boards. “That’s where board diversity is so valuable—it helps a company understand the populations that they serve.”

Jennifer Carolan, a founding general partner at Reach Capital, agrees. “When rubber hits the road, [observing board members’] vote doesn't matter. If you can’t influence the board of directors on a position, you don’t have a vote that matters.”

Going Public

A startup’s first board usually consists of a founder (often the CEO) plus outside investors who can require a board seat in return for putting their dollars into the company. Startups typically keep boards small so they can be flexible and responsive when companies face pivotal decisions—not to mention giving the CEO more control over strategic direction.

Quazzo points to this as part of a pipeline problem: “If the founders aren’t women and the investors don’t include women, then you won’t see women on the board.”

Nothing, however, prohibits a startup from negotiating with investors to include additional boards seats, including non-investors. Gero explains that as companies expand their boards, they have a ripe opportunity to add more diverse voices. Her organization is in the midst of a national campaign to increase the percentage of women on public company boards to 20 percent by 2020.

“You don’t have to get rid of a one person’s seat, just add another seat. But companies are reluctant to do that,” says Gero.

Where that trend tends to change, she says, is when companies go public and are legally obligated to have independent board members. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, passed by Congress in 2002 in response to corporate fraud scandals, requires CEOs and CFOs of public companies to certify that their company’s financial reporting is accurate. It also required that a majority of a company’s board directors be independent.

Whether or not the rule has had any effect on board diversity is difficult to measure, but data shows that women representation is improving for public traded companies. According to the 2020 Gender Diversity Index, 18.8 percent of board seats for companies on the 2016 Fortune 1000 list are held by women—up from 17.9 percent the year prior and trending toward the organization’s goal.

Even as more women have been added to corporate boards, improvements are not happening equally: White women are experiencing these gains before women or men of color. Another study on the 2016 Fortune 100 companies shows nearly 19 percent of board seats were held by white women, while about 13 percent were held by minority men and less than 5 percent were held by minority women.

Adding Diversity Early

Company founders who have added more diverse voices to their boards say their companies are benefiting as a result.

In each case, he says the additional members have added fresh value to his company.When digital education company 2U got started in 2008, the board consisted of three white men. Since going public in 2014, says cofounder and CEO Chip Paucek, the company’s board has expanded from four to 10 members. Of those six new members, half are people of color and two are women.

“Having their voices on the board brings different perspectives. I am a first-generation college student, that’s my life and the perspective I can bring to the table,” says Paucek. “But 64 percent of the students in our program are female. How can we serve them well if there aren’t women on the board?”

While companies can add new board members, Poulson underlines that shifting a company culture to one that embraces diversity can be difficult after a company has grown and matured.

“It’s easier to change and be agile when things are small. When you get to a certain size it’s hard to move and set the culture,” she says. “And if a board has one woman, it’s more likely to have more.”

Paucek admits this will be a challenge going forward for his company, but one that his board is actively thinking and talking about.

“Would it have been better to have people of color and women on our board early? Yes, no doubt. But we addressed it as we could, and I don’t think we are done,” he says. “Do I think two out of 10 [women on the board] is good? No, I don’t. We need more diversity overall on the board.”

To get there, Quazzo believes it’s going to take more than just a few women climbing the ranks in VC firms. She says the firms will have to be more intentional about making changes from the top.

“This goes back further to the people investing in funds. People providing the money must get more forceful about requiring investment committees to be more diverse,” Quazzo says. “Until that happens you won’t see big changes [in board diversity].”

This story was updated on August 2, 2017 to reflect more recent data.