In the past few months, hurricanes have flooded Houston, battered parts of Florida and left a trail of destruction across the Caribbean. Throughout October, wildfires swept through California wine country, damaging more than 14,000 homes and causing billions of dollars in damage.

It’s been a bad year for many communities across the country—and the schools that serve them have not been exempt.

“We were out of school for two weeks,” says Barbara Nemko, county superintendent for Napa Valley Unified School District. “The first week because of the fires; the second because the air quality was so bad.”

At the recent EdSurge Fusion conference, Nemko joined other district leaders who have lived through recent natural disasters to share stories of loss and rebuilding, as well as their best tips to help others plan for the unpredictable.

Have a Plan and Follow It

In the case of Hurricane Harvey, there was enough advance notice to give the city’s schools a little time to prepare before it struck. Houston ISD already had a hurricane readiness checklist, and followed it to the letter, says Lenny Schad, the district’s chief technology information officer.

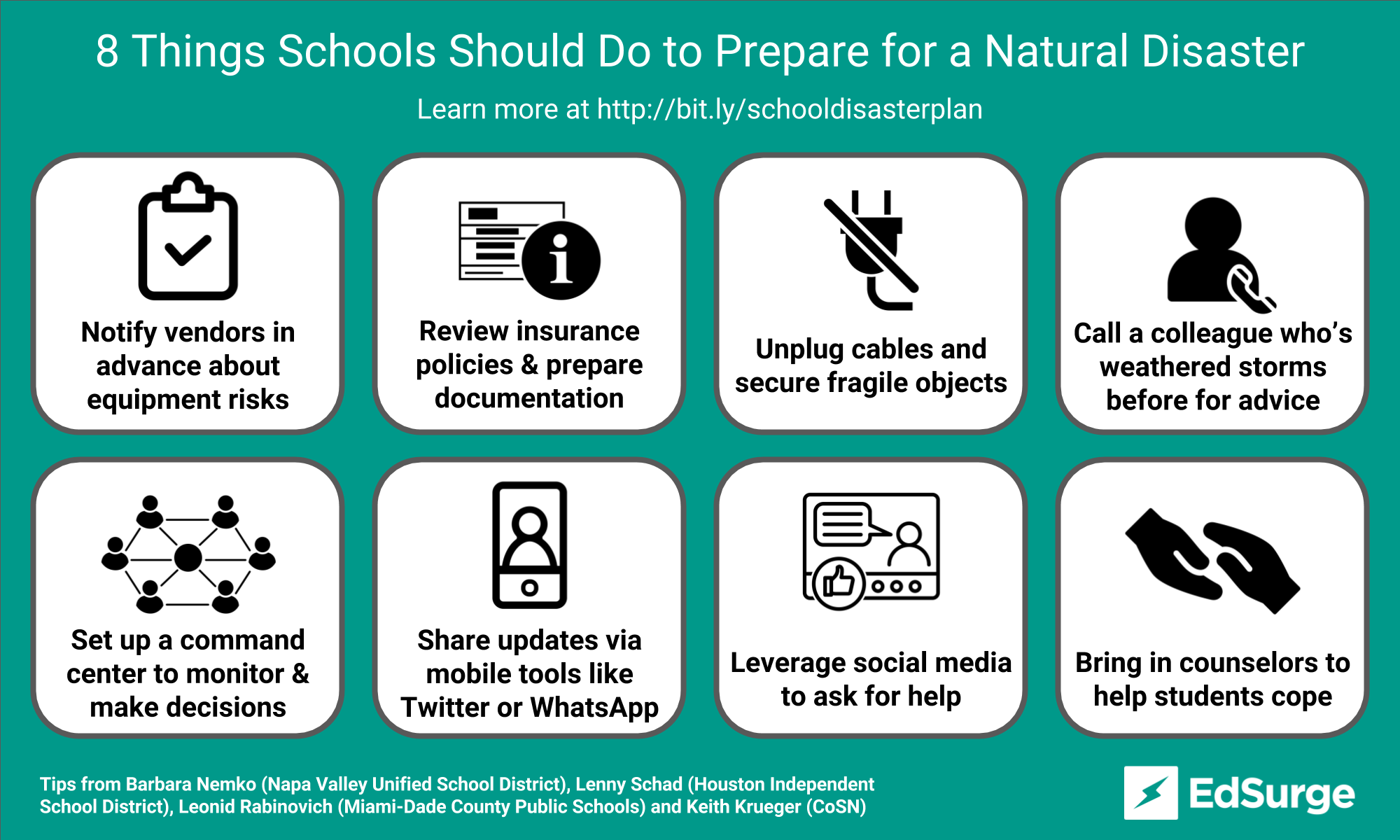

On that checklist are tasks that must be completed 72, 48 and 24 hours before the storm. Among them: contacting vendors to put them on standby in case any equipment is damaged and needs replacement, as well as unplugging and moving low-lying equipment onto tables and shelves. Staff also reviewed insurance information and FEMA procedures.

The time to review policies is before a disaster strikes, Schad says. Insurance companies often need data—in the form of photos and reports—when claims are filed. But types and formats may vary. “For insurance, you need to make sure you’re tracking the info correctly and putting it into a format where the insurance company can actually leverage the data coming in. Having someone proceduralize it and put it into the right forms streamlines the process.”

Prepare What You Can In Advance

More than a decade ago, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, the Consortium for School Networking (CoSN), a school IT association, realized that most school districts were not prepared to deal with IT crises in their areas, according to CEO Keith Krueger. “Even moreso today, tech is not an ancillary thing,” he says. It runs payroll and learning. You need to prioritize what’s important.”

For that reason, CoSN created a 10-step checklist for disaster recovery planning, and updates it regularly as districts learn new lessons in the aftermath of their own emergencies.

“Water damage is the No. 1 challenge that FEMA says occurs from natural disasters,” Krueger says. After floods, cables and wires may not be safe to use, he adds, so a new one-page planning document was recently added to cover the issue.

District leaders say that the only time to plan is beforehand; during the disaster there is not much to do but ride it out. “Believe it or not that was probably the calmest time from a staff perspective because we really couldn’t go anywhere, and we’re just monitoring the storm,” Schad says. “Once the storm clears, and you have an opportunity to get out, that's where the chaos breaks.”

Know Who to Call for Advice

Shortly after Harvey, Florida began preparing for Hurricane Irma. Although Miami was spared a direct hit, the district still prepared for the worst, says Leonid Rabinovich, executive director of the department of instructional technology at Miami-Dade County Public Schools. Among the items on its pre-storm checklist was to place a call to Lenny Schad to compare policies and glean insights from Houston’s experience. In the end, it proved invaluable.

“No matter how much you prepare for an event, people who have already gone through a disaster like that will always have something to offer that you wouldn’t have thought about,” Rabinovich says. “Our CIO has a good friendship with Lenny Schad. Thanks to Lenny, she said that we avoided a lot of problems we didn’t anticipate.”

Make Decisions Together

In some situations, there is simply no time to plan. For Nemko’s county the fires flared up on a Sunday night and by Monday morning “it was a disaster,” she says. Her region had experienced sudden emergencies in the past—mostly earthquakes—and understood the value of making quick decisions.

“It was in some ways simple,” Nemko says. “We knew schools had to be closed.” In a county with six different superintendents, the potential for miscommunication was big. However, teams at every district in Napa Valley county were in constant contact and decided to make official decisions, such as when to close schools, together as a team.

Communicate Effectively

During the days of uncertainty before and after Hurricane Irma, Miami-Dade kept the lines of communication as open as possible. Beyond issuing alerts to local media, the district used its phone trees to send out automated notifications to parents, while superintendent Alberto Carvalho updated his Twitter account regularly. Inside the district, staff traded phone numbers but also worked out alternate means of communication, choosing the popular messaging application WhatsApp.

Since many families ended up evacuating the region, the district also encouraged students and teachers to connect directly when they couldn’t be together physically. “One of the lessons we took from this was to be more proactive than reactive in terms of how we can capitalize on the power of technology to get kids back to learning,” Rabinovich says. “It took people a couple of weeks to get [them] back to Miami, so we wanted to have some learning going on.”

Don’t Be Afraid to Ask for Help

“While you want to be the provider of information, you can also use Twitter and Facebook as an avenue to get help,” suggests Schad. During the height of the post-storm crisis, Houston ISD used its social media channels to reach out to its community. But instead of looking for material donations, they asked for volunteers, specifically those with technology expertise to help district teams assess post-storm damage. Just 16 hours after posting its call to action, more than 300 volunteers had offered assistance. The extra manpower made a huge difference as schools were able to complete inspections and reopen faster.

“Don’t be afraid to leverage [social media] for help, because you have everyone from your community wanting to step in,” Schad says. “It's a two-way process.”

Help Students Cope

When students finally returned to school in Napa Valley, the district was waiting for them with counselors from mental health agencies to help them deal with the effects of trauma and loss.

“For the most part, it was a very joyous return,” Nemko says. “The schools were not damaged and the kids were so happy to get back.” Still, the district is planning a workshop for both parents and students on how to deal with trauma. Even if students didn’t lose their home, they were still impacted, Nemko says. “The entire city of Calistoga was evacuated. To be suddenly awakened from a deep sleep at 2 a.m. by fireman banging on the door and then ending up at a shelter—this was traumatic.”

Prioritize Staff Needs, Too

Despite the poor visibility and air quality, Napa county’s central education offices were never in danger during the wildfires. That allowed a skeletal staff to come in and perform essential functions, among them the county’s payroll. “The last thing we wanted was for teachers who may have lost houses to not even get their paychecks on time,” Nemko says.

In Houston, a command center was set up to monitor the storm and make critical decisions. Provisions for food preparation and essentials were made for them and, before the storm hit, staff were told to go home. “Prior to the storm hitting, those individuals who were going to be there, we let them go home and take care of their families,” Schad says, “because we knew they wouldn’t be there for them.”