Edtech startup, Junyo, started off with a flourish about 15 months ago: its chief executive, Steve Schoettler, left the high-flying social game company Zynga to devote his time to education. He was at the beginning of a wave of enthusiasm for applying the tools of "big data" and data analytics to education. He swiftly pulled together a strong team and won seed funding from the likes of NewSchools Venture Fund.

Now comes "the pivot."

Within the past two weeks, Schoettler has had to make some uncomfortable phone calls to his four blended learning education partners, which together represent 11 schools. Junyo's changing its plans, Schoettler told them. If they wish, Junyo will continue to support them through the end of the school year (next June) or refund their money. But instead of working directly with schools, Junyo is refocusing its efforts around building tools for analyzing data on student performance.

It's the kind of change that happens frequently in tech businesses but it rattles schools and with good reason. At the Education Innovation Summit held at Arizona State University's Skysong campus last April, Chris Lehmann, who runs the Science Leadership Academy in Philadelphia, was one of the few educators in a sea of 800 business leaders, government leaders and philanthropists. Even as business leaders talked up the need for revolutionary change, Lehmann reminded them that education has a pace--and set of requirements--all its own.

"Sometimes teachers get burned," Lehmann said at the meeting. "When companies whose tools we use go out of business, parents turn to us and say, 'What are you going to do about it?' Responsibility for students falls on us. Companies have got to be willing to work with us on that."

Educators reached by EdSurge say they're still assessing what the changes will mean. (One has decided to take the refund.) Schoettler says he's committed to working with the schools to help them make smooth transitions to other vendors. Up through December, Junyo will continue to add new features and improvements to the platform it offers to schools. "We want them to have continuity of service and a smooth transition to another provider," Schoettler says.

Such changes, happening just as the school year takes hold, nonetheless add extra burdens to teachers, forcing them to scramble to rethink plans.

So what happened?

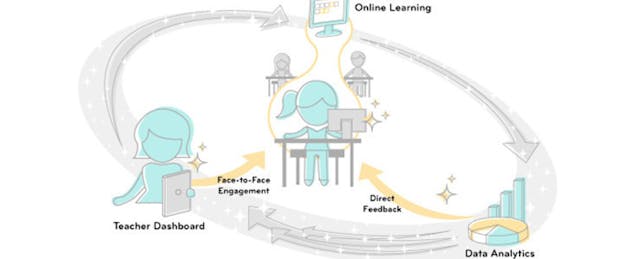

Schoettler says the original vision for Junyo was to use sophisticated data analysis to better understand individual students' needs, abilities and interests. Junyo wants to help answer the question "what should students do next?" and it wants to help teachers learn to use data and feedback to continually improve teaching practices and learning experiences. Over the past 15 months, "we've confirmed, over and over again, that [such data analysis] is important," he says.

Creating a tactical plan to deliver on that promise, however, turned out to be a thorny problem.

One typical approach for high tech companies developing new products is to identify a lead customer or two to work with closely to help define the product. A bevy of schools lined up to work with Junyo, which signed up four leading blended learning partners: Rocketship Education, Kipp Empower Academy in Los Angeles, Touchstone Education, and Oakland Unified (which had two schools, Elmhurst and Encompass).

Although the schools were already using technology products, they needed more technological underpinnings before they could effectively study student performance. Among them: a "single sign on" system that would let teachers and students get to work by logging in once rather than multiple times; classroom management systems that organized incoming data; ways to represent or visualize data. There were not effective APIs or standards for programs to share data. And off-the-shelf technology solutions for such problems were scarce, Schoettler says.

Junyo adapted its strategy: rather than just focusing on data and analytics, it would build a platform for its partner schools. (It did have at least one competitor, another NSVF-funded company, EdElements.)

"We recognized all along that there were hurdles," Schoettler says. "Some of the hurdles we were willing to go over." For instance, collecting data is most effective when the "learning objects" are narrowly defined. Junyo consequently started atomizing the Common Core requirements--breaking them down into tiny chunks that could be assessed in minute detail.

The further Junyo travelled down the path of creating the underpinnings that would support its efforts to collect and analyze data, the more executives worried that few of those efforts would tap the large volumes of data that analytics engines need to work effectively. Junyo's partner schools took different approaches to blended learning and so needed their systems to work slightly differently. "If we continued to provide for the needs of schools, we wouldn't have the resources to build strength in analytics," Schoettler says.

The ambiguities in Junyo's strategy caused unrest. In April, one of Junyo's founding team members, Eric Berger who was vice president of engineering, left. (He has since joined edtech startup, Desmos.) In August, another cofounder, Matt Pasternack, jumped to Clever, which was founded to tackle a specific, vexing problem that schools face (namely, how to connect independent software products with school's student information systems). Then as Junyo refocused on its analytics mission in September, cofounder Kim Jacobson stepped out of daily management. (She remains part of Junyo's advisory board.)

"People leaving startups is part of the space," says Schoettler. Junyo still has a full time staff of 16 including many with teaching backgrounds and engineering chops. "The team we have is a good group for moving ahead on analytics, even if we're spending less time with schools directly."

With its renewed emphasis on data and analytics, Schoettler expects Junyo to partner with companies that are involved in creating or handling large volumes of data, such as publishers, those who build assessment systems, and even online schools.

"A lot of existing partners tell us they wish they had time to present data in ways that are impactful," Schoettler says. "The market will be better served if partners could split the work and together take care of the needs of schools going down the blended learning path."

NSVF's Wayee Chu says she believes that refocusing on analytics is the right path for Junyo. "This is hard work. Steve has tried to be very thoughtful and immerse himself in the needs of schools. He's given me confidence that he will make this transition as seamless as possible."

It's easy to say technology involves risk--another thing to experience it. Now these blended learning programs are getting testing, perhaps sooner than expected, on one of the greatest challenges posed by new technology: just how flexible can these early adopters be?